by Vanessa Formato

All these fruits are dying. Wisps of grey mold stretch out from the bottom of a sickly, shriveled strawberry. Plums blush an unnatural shade of teal. A pockmarked peach hangs from a branch, the bark discolored, its …

All these fruits are dying. Wisps of grey mold stretch out from the bottom of a sickly, shriveled strawberry. Plums blush an unnatural shade of teal. A pockmarked peach hangs from a branch, the bark discolored, its …

Featuring profiles of outreach & advocacy in cultural heritage

by Vanessa Formato

All these fruits are dying. Wisps of grey mold stretch out from the bottom of a sickly, shriveled strawberry. Plums blush an unnatural shade of teal. A pockmarked peach hangs from a branch, the bark discolored, its …

All these fruits are dying. Wisps of grey mold stretch out from the bottom of a sickly, shriveled strawberry. Plums blush an unnatural shade of teal. A pockmarked peach hangs from a branch, the bark discolored, its …

by Jonathan Fryerwood

The RAINBOW ARCADE exhibition hosted at the Schwules Museum in Berlin presented itself as the first major exhibition of queer content in video games. The event ran from December 2018 to May of this year. The project …

by Lindsay Olsen

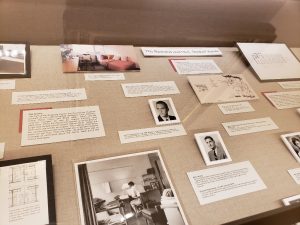

All across the Cambridge campus from February to July, Harvard University is  commemorating the birth of Bauhaus, the modernist school of art founded by German designer Walter Gropius in 1919. Events are on the calendar showcasing some …

commemorating the birth of Bauhaus, the modernist school of art founded by German designer Walter Gropius in 1919. Events are on the calendar showcasing some …

by Hannah Elder

The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum was created as the vision of its founder and namesake. Isabella Stewart Gardner created the museum as an aesthetic space, surrounding visitors with beauty and inviting them to think about the ways …

The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum was created as the vision of its founder and namesake. Isabella Stewart Gardner created the museum as an aesthetic space, surrounding visitors with beauty and inviting them to think about the ways …

by Alden Ludlow

About a year ago I was tasked with putting together an exhibit for the small reading room at the Wellesley Historical Society. Having just reorganized and processed our Picture Postcard Collection, I decided it was ripe …

by Ariel Barnes

The Rihanna Experience at the Museum of Science, Boston is a planetarium show unlike any other. For $10 visitors can listen to the greatest hits of Rihanna while being dazzled by a light show projected onto the …

by Jessica Chapel

You can’t cut an American president out of history. How, then, do you represent a president driven from office in disgrace and his complicated legacy? During a recent California trip, I took a detour on my way …

by Jessica Hoffman

Two large metal mushrooms loomed above me, barely obscured by the thin shield of wiry threads fencing them in. The room glowed with an otherworldly light. The air crackled with spiraling energy. Suddenly, the loudest noise I’d …

by Anna Faherty

Lorna Condon, the Senior Curator of Library and Archives at Historic New England, was kind enough to meet with me this week and tell me about the collections and programs her institution offers. In her position of …

by Nicholas Glade

The Owls Head Transportation Museum is a unique institution; therefore, it needs an archivist willing to step up to a variety of tasks and challenges. Enter Sarah Dunne! As a head Archivist, she performs a wide …