by Alden Ludlow

About a year ago I was tasked with putting together an exhibit for the small reading room at the Wellesley Historical Society. Having just reorganized and processed our Picture Postcard Collection, I decided it was ripe for use, featuring many images of a long-past Wellesley. The original exhibit morphed in unexpected directions. I have been able to adapt it for uses in different contexts, and it is becoming a versatile, expandable advocacy and outreach tool.

Our reading room is really a reading room in name only. It is a small, approximately 300-square-foot, multi-use space. Researchers do their work here; collection accession and processing occurs here. It serves as a lunchroom and as a space where the board of directors and various committees meet. As such, most of the people who spend time in the space are board members, volunteers, and staff. It is more of an “in-reach” space than an “out-reach” space.

My first task was to select postcards for the exhibit; my plan was to put enlargements of postcards on the limited wall space, and fill the display cabinet with items reflecting the related elements of postcard production and postal history. I developed selections based on three criteria, and ended up with about 25 enlarged postcards and a number of items for our small display cabinet.

First, the most interesting postcards were those manufactured during what has been called the “Golden Age of Postcards,” 1907 to 1915. Changes in postal regulations regarding the content and presentation of postcards led to an explosion of inexpensive, artistic cards featuring local landmarks all over the country. Many of the cards were manufactured in Germany, and World War I led to the decline in their quality and popularity.

Second, I wanted to highlight postcard use during that time. Often called the “postcard craze,” this time period found people using the cards much as we use social media today. At the time, most of the writers of the cards were educated, upper-middle class women. Wellesley, a wealthy town, with the added prestige of Wellesley College, was exactly the demographic postcards appealed to. My criteria were that the cards had to have correspondence written on them, which I could use to highlight the social situation of the time. The correspondence provided a window into the context of a limited span of time and space. Also, by 1903, Kodak had developed a camera which could take pictures that could be directly printed onto a postcard back; we had a number of these unique cards, portraying people from the town (including the 1913 Wellesley High School football team). These cards were exchanged or mailed to friends, usually within the town, and their uniqueness added a personal element to what was generally a mass-produced industry even then. I also obtained one of the cameras at a sale, to further enhance the display cabinet.

Third, I felt a number postcards chosen for the exhibit should challenge viewers in some way. Initially, I thought it would be difficult to “problematize” a postcard exhibit, but as I looked at the cards, it became clear that many of the buildings depicted had been torn down, some of them in recent years. Adding a subtle twist to the choices, I was able to highlight much of Wellesley’s lost architectural heritage. Later, I found out that the Wellesley Historical Commission found this highlighting less than subtle. Success! I managed to make a postcard exhibit controversial!

Once the exhibit was up, I immediately started planning a way to “capture” and archive it; I figured it would be up for a year or two. I put together a simple PowerPoint presentation in a way that reflected the flow of the exhibit, and captured all of its textual and artistic elements. Since we had the cards enlarged for use, we had high-quality scans of the images and related correspondence elements. I took photographs of the artifacts in the display case. This record of the exhibit was intended to be archival; it would come alive later on.

I had put together the “catalog” of the exhibit on my own time, and once I was finished with it I sent it to our executive director, and curator, so they would have it as a record of the exhibit. Board members were pleased with the exhibit, and at some point, the “catalog” circulated among them.

I began to ruminate. We didn’t have the funding to produce a real exhibit catalog, but I began to think about reworking the catalog into a more colorful presentation which I could then present to the board and volunteers. Sort of a slide show of the exhibit, but with added elements and without the limiting constraints of four walls. I could literally “spread out” and add elements, and better organize the flow of sectional elements I had incorporated into the exhibit (People/Vanished Buildings/The Great Outdoors/Postcard History and Use).

As I was thinking about these things, I was not aware that my archival “record” presentation was making the rounds with board members. I suspect some confluence of shared board members between institutions led David Ball, the executive director at the Spellman Museum of Stamps and Postal History, and Henry Lukas, their education director, to contact me about doing a presentation based on the “catalog” I had created.

Philatelists know the Spellman, but the museum, sitting on the bucolic campus of St. Regis College in Weston, has an international reach and a successful local all-ages education program. Stamp collecting may appeal to a small segment of the population, but the topics postage stamps cover is vast; it is this subject-based approach which is at the core of their programs. They were interested in the postcard exhibit on many levels, particularly from a postal history perspective.

I set out to revamp the postcard PowerPoint into a full-fledged presentation, separating text from images, pulling quotes from correspondence for the individual slides, and adding images of the reverse of many of the cards. Having been a stamp collector as a youngster, it was easy for me to add a section to the presentation on how stamp and postcard history overlapped.

By September 2017, I was ready to go, with a 45-minute presentation which covered Wellesley history, stamp collecting, postcards and postcard history, the social context of postcard use, and actual correspondence from the cards. The early decision I had made to use only postcards which had been used as correspondence paid off. The small reading room exhibit had morphed into a compact yet comprehensive presentation, its scope and content widely expanded.

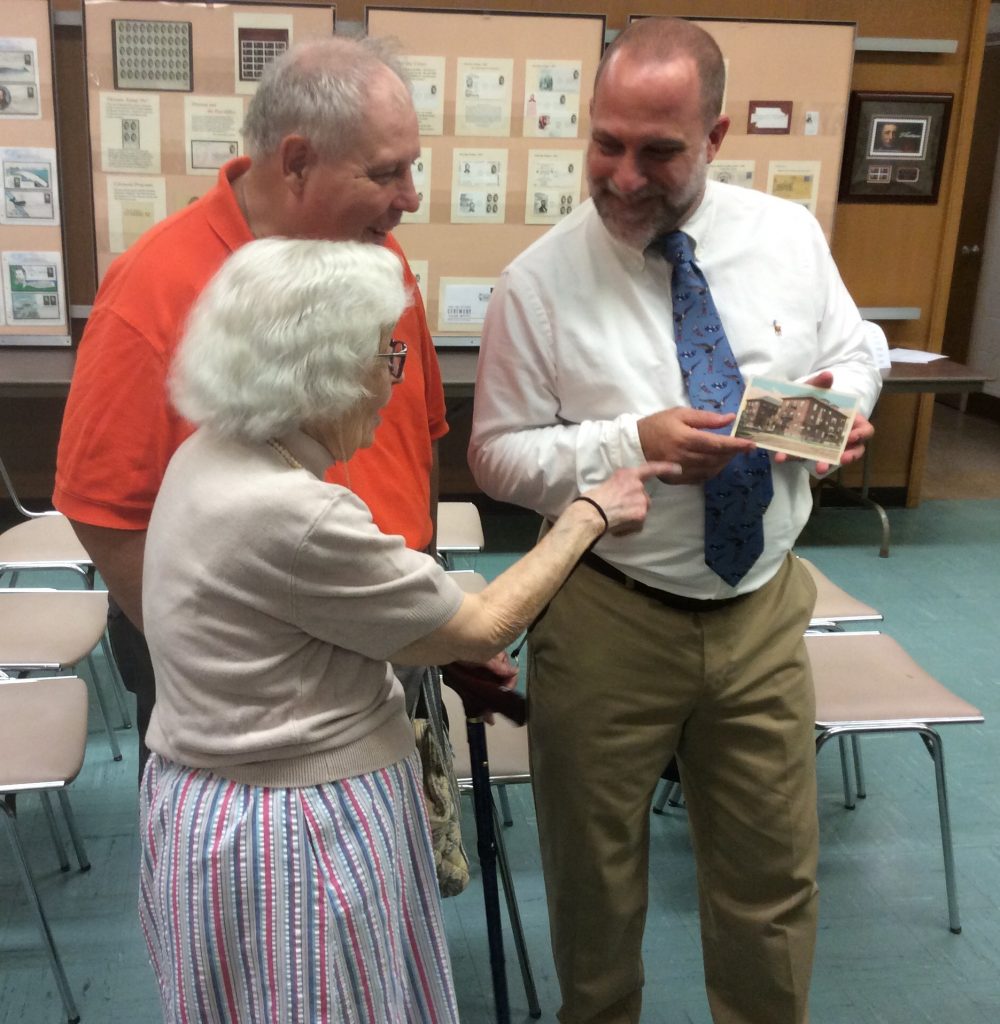

The evening of the presentation at the Spellman I realized that this collaboration was a perfect fit: the audience of about 45 included philatelists, amateur historians, and postcard collectors. The time I had spent processing the collection, putting up the exhibit, and assembling the presentation was crucial in being able to make the presentation an interactive experience; I was open to questions, had the answers, and lively discussion was incorporated into the process. The presentation ended up being over an hour. Many of the people who had attended brought postcards and stamps with them, and this led to an informal show-and-tell reception.

Sometimes collaboration is planned, sometimes it is serendipitous, as it was in this case. I kept pushing the boundaries of our small exhibit, and new opportunities presented themselves. While the exhibit and the eventual presentation were steps removed from encountering the postcards as primary sources, the process was in keeping with the education mission and vision of the Wellesley Historical Society. The collaboration with the Spellman allowed for expansion of the presentation for broader outreach, sparking interest from people of different, yet overlapping, interests. In discussions following the presentation, it was clear that what I had done could be replicated for surrounding towns.

While the outreach impacts of the presentation are easily measured, what is less easy to quantify is how the success of the presentation has looped back around and has made staff advocacy within the Society’s board of directors easier. Often boards have a difficult time determining what archivists do, but when they pick up the newspaper and read about the impact a presentation had within a segment of the population, the educational mission seems clearer. Additionally, they have become more open to new ways of doing things with the collections to broaden the audience.

In a final note, my “poking” of the Wellesley Historical Commission has taken a turn. Initially unhappy that I subtly suggested they were not capable of their role in historic preservation, they have now expressed an interest in having the presentation at one of their meetings. We may soon see if I am up to the task of doing outreach in the Lion’s Den.

Resources

Wellesley Historical Society: http://www.wellesleyhistoricalsociety.org/index.htm

Spellman Museum of Stamps and Postal History: https://www.spellmanmuseum.org

Wellesley Historical Commission: http://www.wellesleyhistoricalcommission.org

Smithsonian postcard history: http://siarchives.si.edu/history/exhibits/postcard/postcard-history