by Emily Murphy

Can you fit an archivist in a backpack? With this provocative question, the team at the Community-Driven Archives Project seeks to break down barriers preventing entry into the field of archives. At the root of the question …

Featuring profiles of outreach & advocacy in cultural heritage

by Emily Murphy

Can you fit an archivist in a backpack? With this provocative question, the team at the Community-Driven Archives Project seeks to break down barriers preventing entry into the field of archives. At the root of the question …

by Alex Howard

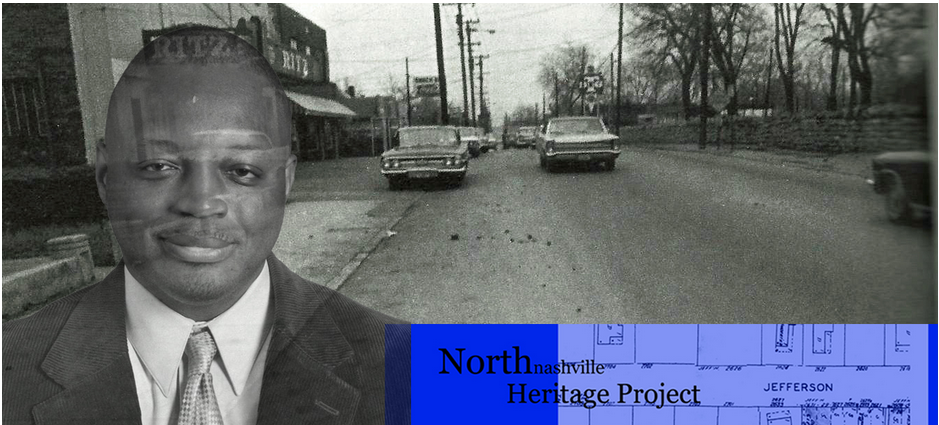

“The North Nashville Heritage Project taught me that the old lady who fried chicken at the church was just as important as the lawyers who bailed the students who got arrested out of jail,” said Dr. Learotha …

by Ashley Williams

“Can We Talk” is a podcast put on by the Jewish Women’s Archive. The JWA is  an organization based in Brookline, Massachusetts that is dedicated to the celebration and documentation of Jewish women and Jewish feminism. Their …

an organization based in Brookline, Massachusetts that is dedicated to the celebration and documentation of Jewish women and Jewish feminism. Their …

by Alden Ludlow

About a year ago I was tasked with putting together an exhibit for the small reading room at the Wellesley Historical Society. Having just reorganized and processed our Picture Postcard Collection, I decided it was ripe …

by Jenny DeRocher

La Crosse, Wisconsin is a city of about 50,000 people. It sits between tree-covered bluffs and the winding Mississippi River. The city’s downtown area is like many other industrial Mississippi River towns with traces of train tracks, …

by Adam Schutzman

Snowden Becker has been actively involved in outreach and advocacy for most of her professional career. She has been working in the cultural heritage field for over 20 years and is perhaps most well known for her …

by Anna Faherty

Lorna Condon, the Senior Curator of Library and Archives at Historic New England, was kind enough to meet with me this week and tell me about the collections and programs her institution offers. In her position of …

by Erica J Hill

K.J. Rawson is the director of the Digital Transgender Archive, an online platform providing digital versions of transgender historical records, born-digital records, and holdings of other repositories around the world. Despite not having professional training in …

by Victoria Jackson

In a world full of constant content generation, how can library and information science professionals convince their communities, their institutions, and the world at large of their importance? It is a question of growing importance within the …