by Jessica Chapel

You can’t cut an American president out of history. How, then, do you represent a president driven from office in disgrace and his complicated legacy? During a recent California trip, I took a detour on my way from Los Angeles to San Diego to ask those questions.

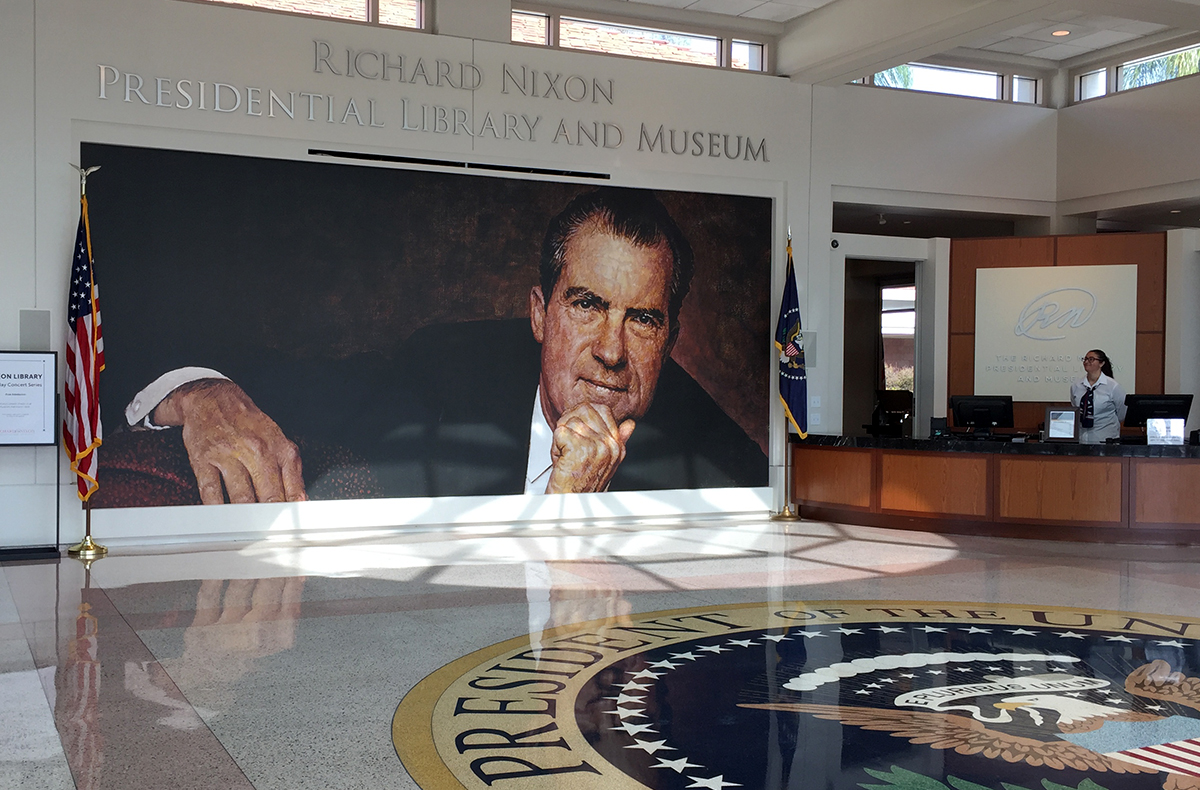

The Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum opened in Yorba Linda — a one-time farm town in Orange County — in 1990, 16 years after the 37th president became the first president to resign from office. Unlike every other president since Franklin D. Roosevelt, Nixon did not plan to donate his library to the National Archives. It was a privately run institution supported by the Nixon Foundation, holding the president’s diaries and his pre-presidential papers.

Congress controlled his administration’s records, more than 44 million pages of documents, plus photographs, film — and the infamous tapes. The 1974 Presidential Recordings and Materials Act gave custody of the presidential files to the Archivist of the United States, a move intended to thwart any destruction of records from Nixon’s scandal-blighted presidency.

Feelings about Watergate and Nixon’s record were still running high when the library opened and museum director John Taylor postponed making two Watergate tapes available. Historians complained about the withholding of materials as much as they did the slant of the exhibits and the presentation of the one Watergate tape incorporated into a display, a decision that Taylor defended as a matter of serving visitors.

“The fact that we are the Nixon library does not deprive us of the ability and indeed the responsibility of placing the information we present in some historical context,” he told the New York Times. “Some people use the word ‘cover-up,’ and what they’re saying is that in fact they do not wish for the Nixon library to put forth its interpretation of this document.”

In 2007, after decades-long legal wrangling, the National Archives assumed administration of the Nixon library and museum, and the presidential records were moved to Yorba Linda. The transfer culminated in a wholesale renovation of the exhibits that closed the museum for a year, a joint project with the Nixon Foundation. The museum reopened to the public in October 2016.

One year later, I was waiting with a dozen other early birds on a Sunday morning for the library’s doors to open. I wanted to see how the revamped galleries told the story of a president whose name has become synonymous with abuse of power, a politician who has been both pop culture joke and high culture inspiration, the subject of numerous biographies, and a man who attempted to craft his own myth from the first sentence of his 1977 memoir: “I was born in a house my father built.”

The conflict in how Nixon figures in cultural memory is matched by a seeming conflict in how the dual keepers of his library and legacy manage outreach and advocacy.

On the Nixon library social media channels managed by the Nixon Foundation — Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, and Snapchat — posts tend toward Nixon’s acknowledged successes, White House events, and happy family moments. Most of the comments on these channels are positive, but there are instances when followers misunderstand who is posting and why: “If you knew the month and date why didn’t you include it instead of all those unnecessary hashtags?,” one commenter asked on Instagram, seeking the original date of a photo. “We are not an archival page,” the account replied.

Earlier this year, a Nixon library tweet was interpreted as trolling president Donald Trump, prompting a public rebuke from the National Archives.

The Nixon library social channels were also used to question the work of filmmaker Ken Burns, whose Vietnam War documentary aired on PBS in September. “There is no factual support for anything in this sentence,” read one Instagram post, referring to a point on page 347 of the companion book to the film.

Both the National Archives and the Nixon Foundation maintain web pages for the library and museum. The .gov site is oriented to researchers, with information on newly released materials and upcoming events. The .org site is a slicker home for the foundation’s other programs in addition to the library and museum. It was the Nixon Foundation that used its site to respond to Nixon biographer Jon Farrell, who — citing a note written by Nixon aide H.R. Haldeman that Farrell found while doing research at the Nixon library — wrote that Nixon subverted president Lyndon Johnson’s peace efforts in Vietnam late in the 1968 presidential campaign.

“Misunderstanding a monkey wrench,” answered the foundation, arguing that Farrell’s interpretation came down to a dash.

Walking through the exhibits, I catch Nixon’s 1972 reelection jingle: “Nixon now, Nixon now, more than ever, Nixon now.” The galleries are bright and interactive. In the Nixon in China room, visitors can pose for pictures with cutouts of the president and First Lady at the Great Wall. At another exhibit, visitors can lift the earpiece of a phone and hear segments of Nixon’s taped calls. Even FDR taped conversations in the oval office, the exhibit tells me. “Tough choices,” blares another, inviting me to struggle — via touchscreen — with the sort of decisions the president had to make.

I come to the Watergate gallery, and if it’s no longer a darkened room occasionally haunted by Haldeman, it is still an unwelcoming room with text-heavy exhibits. I’m not sure who it’s for — amid all the words, the impression is of a reckoning avoided.

Read more:

James Worsham, “Nixon’s Library Now a Part of NARA,” Prologue Magazine, Fall 2007.

Andrew Gumbel, “The Last Battle of Watergate,” Pacific Standard, December 8, 2011.

Christine Mai-Duc, “The ‘New’ Nixon Library’s Challenge: Fairly Depicting a ‘Failed Presidency’,” Los Angeles Times, August 16, 2016.