by Emily Magagnosc

Sara Davis is the Digital Project Manager for the Olmsted Archives at the Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site. As the Site is part of the National Park Service, outreach and public programming is essential and …

Featuring profiles of outreach & advocacy in cultural heritage

by Emily Magagnosc

Sara Davis is the Digital Project Manager for the Olmsted Archives at the Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site. As the Site is part of the National Park Service, outreach and public programming is essential and …

by Jenny DeRocher

Rachel Seale has worked at Iowa State University Special Collections and University Archives as an Outreach Archivist for almost two years. She moved from Fairbanks, Alaska, where she worked for six years as an archivist at the …

by S.S.

Meet Jade Pichette, Volunteer and Outreach Coordinator for the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives (CLGA). Although Pichette’s background in social work might make them an outlier in the archival field, they see this atypical professional experience as …

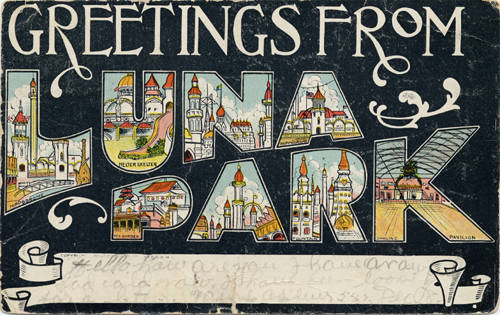

Postcard from the Postcards of Cleveland Collection, part of the Cleveland Memory Project. Credit: Michael Schwartz Library, Cleveland State University.

by Jessica Chapel

When Bill Barrow was a child growing up in Cleveland, an electric sign on the city’s …

by Julia Newman

Currently serving as the Interim University Archivist and Curator of Special Collections at the University of Massachusetts Boston (UMass), Andrew Elder recognizes the importance of outreach and advocacy within the archival field. His entry into the archives …

by Sara Mueller

Three years ago, the archives at Sasaki Associates, an architecture firm in Watertown, Massachusetts, did not exist. Today, archivist Aliza Leventhal works to ensure that the significance of this fledgling archive is seen throughout the firm.…

by Natalia Gutierrez-Jones

I recently had the opportunity to speak with Jessica Lacher-Feldman, who is the Assistant Dean of Rochester University, as well as the Director of Rare Books, Special Collections and Preservation. Jessica discovered her affinity for archives …

by Alden Ludlow

Myron Groover is the Archives and Rare Books Librarian at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. He received his Master of Archival Studies and MLIS degree from University of British Columbia, Vancouver in 2012. He also holds a …

By Hannah Yetwin

Randall Jimerson is the director of the graduate program in Archives & Records Management and professor of history and at Western Washington University in Bellingham, Washington. He is …

By Rebecka Sheffield

I was lucky enough to meet Gillian “Jill” Shaw in 2009, at the University of Toronto iSchool, where we were both students. We caught up again last week to talk about outreach and advocacy in …