by Grace Millet

Native Land Digital, also referred to as simply Native Land, is a digital database and map that contains information about indigenous peoples’ lands throughout the world. Started and led by indigenous activists from around the globe…

Featuring profiles of outreach & advocacy in cultural heritage

by Grace Millet

Native Land Digital, also referred to as simply Native Land, is a digital database and map that contains information about indigenous peoples’ lands throughout the world. Started and led by indigenous activists from around the globe…

by Kai Uchida

Project Website: https://web.stanford.edu/group/chineserailroad/cgi-bin/website/

Digital Materials Repository: https://exhibits.stanford.edu/crrw/browse

Organized in 2012 by Gordon H. Chang and Shelly Fisher Fishkin, The Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project is a project organized by scholars at Stanford University and …

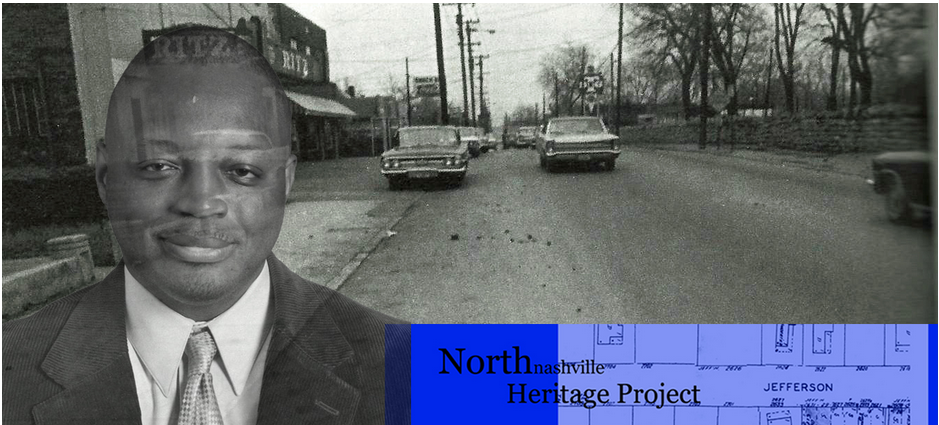

by Alex Howard

“The North Nashville Heritage Project taught me that the old lady who fried chicken at the church was just as important as the lawyers who bailed the students who got arrested out of jail,” said Dr. Learotha …

by Jenny DeRocher

La Crosse, Wisconsin is a city of about 50,000 people. It sits between tree-covered bluffs and the winding Mississippi River. The city’s downtown area is like many other industrial Mississippi River towns with traces of train tracks, …

by Sony Prosper

I recently met with Dr. Kenvi Phillips to discuss advocacy and outreach in the context of a curator working in a research library. Kenvi comes from a rich cultural heritage and history background. She received a bachelor’s …

by Jessica Hoffman

A vast complex sits apart from a main road on the Cape, housing the Mashpee Wampanoag Indian Community and Government Center. Nicknamed “The Castle,” the new building is a state-of-the-art asset, layered with modern architecture, security guards, …

by Erica J Hill

K.J. Rawson is the director of the Digital Transgender Archive, an online platform providing digital versions of transgender historical records, born-digital records, and holdings of other repositories around the world. Despite not having professional training in …

by Victoria Jackson

In a world full of constant content generation, how can library and information science professionals convince their communities, their institutions, and the world at large of their importance? It is a question of growing importance within the …

by Jessica Purkis

Recently, I had the chance to catch up with Bergis Jules, the University and Political Papers Archivist at the University of California, Riverside. Bergis manages UC Riverside’s institutional records, political papers collections, and African American collections. While …

by S.S.

Meet Jade Pichette, Volunteer and Outreach Coordinator for the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives (CLGA). Although Pichette’s background in social work might make them an outlier in the archival field, they see this atypical professional experience as …