by Samantha Pickering

Book banning is a growing issue in the United States, as narrow-minded people attempt to exclude certain titles from library shelves, an assault on which communities and stories are allowed to exist in public. This movement has become organized and systematic. According to the American Library Association (ALA), seventy-two percent of demands to censor books in school and public libraries come from pressure groups and government entities, including elected officials, board members, and administrators: people who have the power to take real action and empty out shelves. Hidden under a veneer of protecting children from subjects that might make them “uncomfortable,” the ALA’s list of most challenged books reveals the stories that are under siege from this movement: those of the LGBTQIA+ community, and those that deal with subjects like diversity, equity, and inclusion, often top the list. Stories that might expose children to a different way of life, or offer a critique of mainstream narratives and histories, are under threat.

I hadn’t been looking to attend an art exhibit when I came across “We Read Banned Books!” I encountered the project for the first time on the Boston Public Library’s main webpage, which I had visited to put some books on hold. The exhibit flashed by on a scrolling menu of the BPL’s featured events. As an avid reader and someone outraged at the growth of book banning in the U.S., I was immediately intrigued.

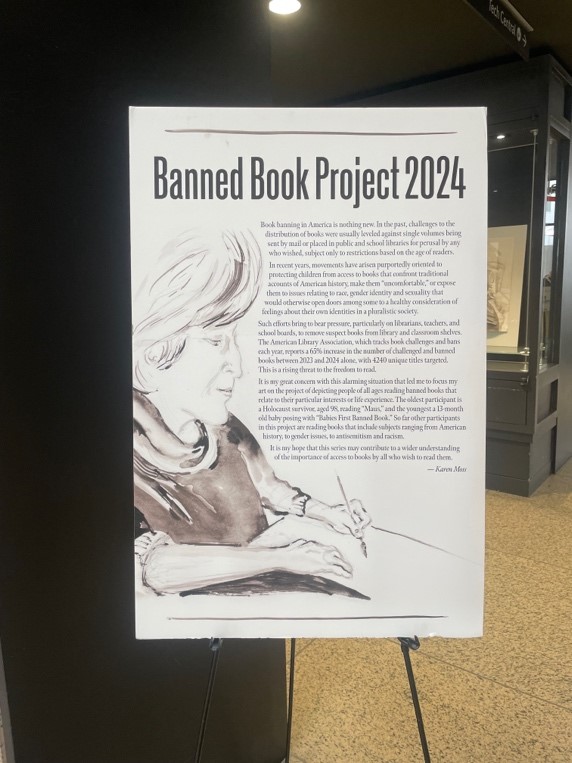

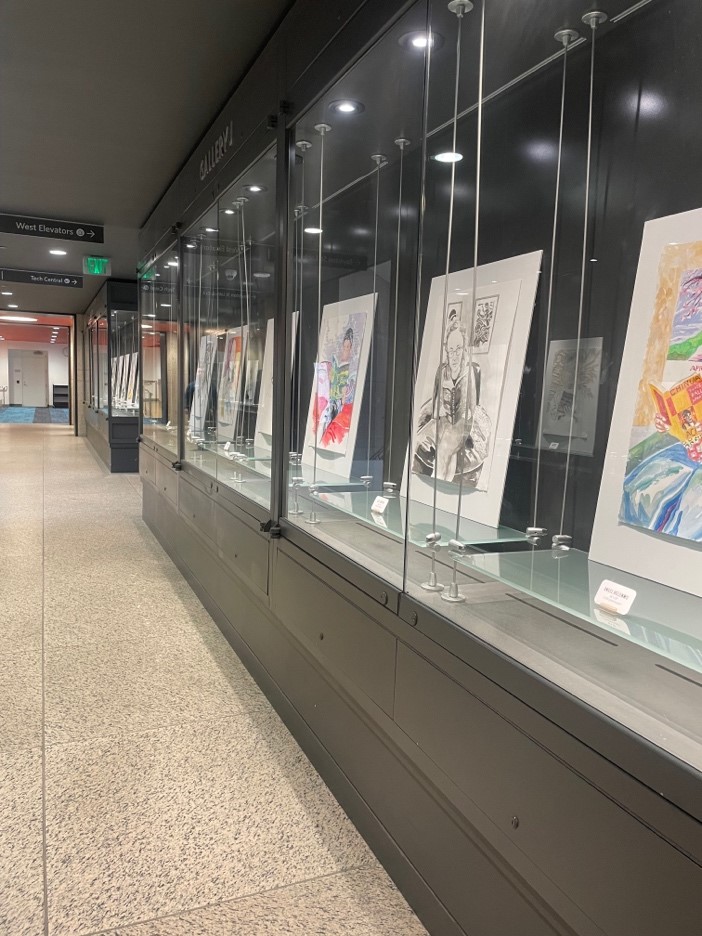

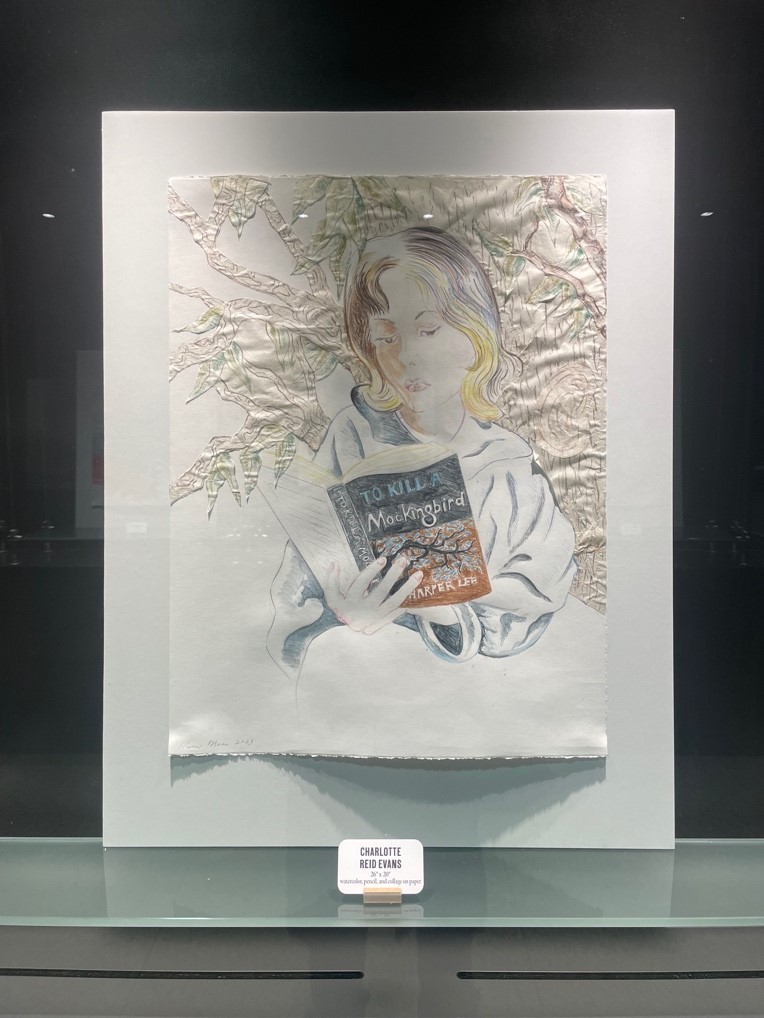

The exhibit sits in gallery J, between the BPL’s printing center, technology center, and fiction section. A sign placed in a doorway introduces the exhibit: outlining the issue of book banning in the U.S., the growing scope of the problem, and the artist’s hopes and concerns. Lining the hall are a series of portraits—black and white, color, and a variety of mediums. There are a variety of people depicted as well: different genders, different races, different ages. They are titled simply with the name of the person in the image.

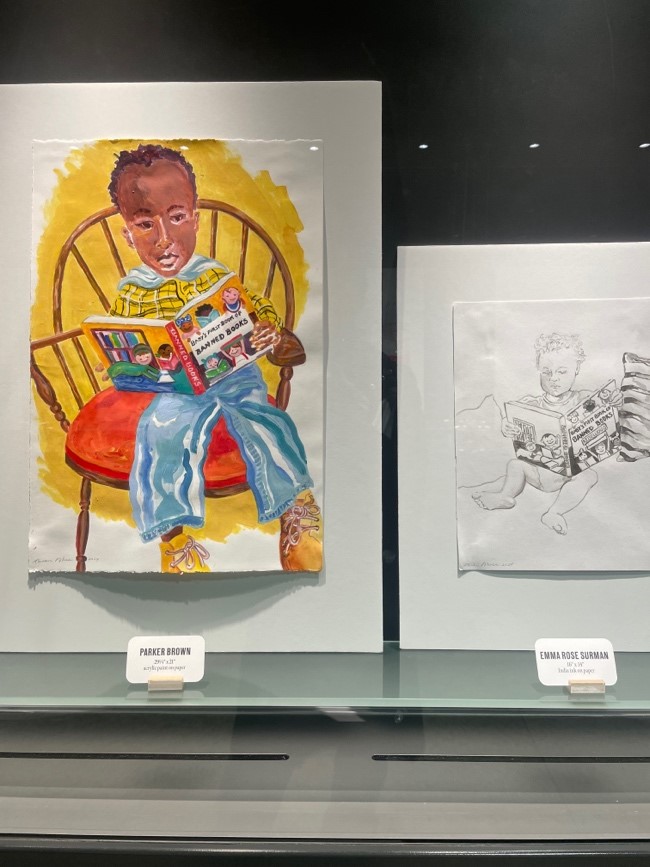

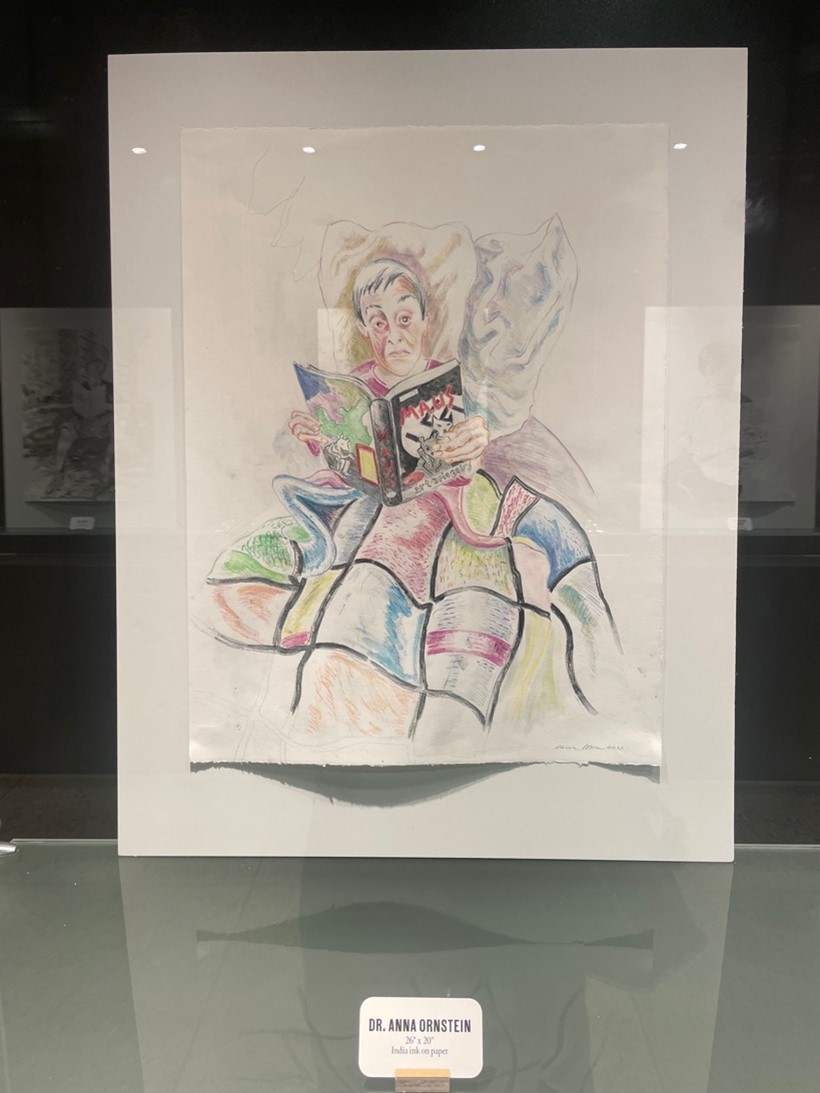

In their hands are books that have been banned sometime or somewhere in the United States. The titles are wide ranging: Macbeth, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, 1984, Maus, The Handmaid’s Tale, This Book is Gay, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, Harry Potter and the Half Blood Prince, To Kill a Mockingbird, and others. All but one are available to be checked out through the Boston Public Library.

The BPL is a fitting host for such an exhibit. Readers and community members who are affected by the problem of book banning walk through the doors of the library every day. Library leadership had in mind a year of focusing on banned books. This is an apt time for such a project: the American Library Association reported a 65% increase in the number of challenged and banned books between 2023 and 2024. Walking through the hall, I was reminded of the urgency of the issue when I saw many books that I loved, and which had a profound impact on me, displayed as banned books. Eager to learn more about how this exhibit came to be, I reached out to Karen Moss, the artist behind the portraits.

Boston artist Karen Moss is well aware of the issue of book banning. She had been collecting newspaper articles about the problem, the basis for a yet unknown project. Moss had just finished an exhibition of portraits at a gallery in the SoWa neighborhood. She eventually came to the idea of creating portraits of people reading banned books. The exhibit required Moss’s persistence to occur; by her own account, library leadership had no idea that she existed. She prevailed, and “We Read Banned Books!” was born.

This is an exhibit born out of community. All of the people Moss depicts are connected to her in some way. Some are family members, others are neighbors, current and former. One of the littlest readers, Parker Brown, engrossed in a copy of Baby’s First Book of Banned Books, was a chance encounter. He and his mother attended an open studio in Somerville where Moss was in attendance: Moss snapped a photo of Brown reading the book on a chair to draw from later.

Some of the readers have extraordinary connections to the books they holding. Kata Hull, holding Our Bodies, Ourselves: A Book by and For Women, knew some of the people who wrote the book. Dr. Anna Ornstein is a Holocaust survivor who spent time at the same concentration camp as the author of Maus, the book she holds. Some of the people in the portraits chose their own books. For others, Moss chose titles from different categories that were the most banned: books pertaining to race, antisemitism, gender, sexuality, and feminism. She wanted to include books that related to her subjects’ particular interests or life experience.

Moss hopes that people who visit the exhibit will take away the idea that everyone should have the right to read what they want to read, and should be grateful that the BPL has those materials available to them. She hopes that people don’t let narrow-minded individuals rule their schools and libraries. She wants them to cherish and fight for their community. She wants people to become warriors.

This exhibit reaches out directly to those who are affected by book banning, those who are walking through the library, maybe on their way to check out a banned book. The diversity of people in these portraits is a reminder of the myriad people who are touched by this issue. People walking through the hall might see themselves, or a friend, or a neighbor, reflected back at them. Maybe someone will see in one of the books a treasured memory of reading or a story that affected them deeply. Moss chose books that related to the lives and experiences of the people in her portraits. As books are so often primed to do, they can reach out to the lives and experiences of the people walking through the gallery as well, reminding them of the importance of keeping these stories available to all.

The exhibit advocates the idea that we are a community joined by a common pursuit: reading. After all, the exhibit is titled “We Read Banned Books.” “We” does not only refer to the people drawn in ink and acrylic in gallery J, but to all of us who walk into the library and pick up a book to read. The exhibit reminds us that we are a community bound together by books, and that we need to fight for our friends, our neighbors, and ourselves, to ensure that our stories are kept on library shelves.

Hopefully, some people will be inspired to check out one of the books or engage more deeply with the issue of book banning. That is the one thing that is perhaps missing from this project: guidance on how individuals can make an impact in the larger fight against book banning. A search of the term “book ban” on the BPL’s website leads to a blog on the topic. The blog highlights titles under attack, providing the reason someone challenged it, a summary, the response to the challenge, and the librarian’s thoughts on the book. There is even a spot on the page where you can place the book on hold or check it out from the library. However, here too there is a lack of information on how the library’s users can push back against the tide of book banning. We as librarians and information professionals need to disseminate this knowledge.

There have long been discussions about issues of objectivity and neutrality for librarians and information professionals; about whether we should be passive observers in a tumultuous political environment. Book banning is an area where librarians and information professionals can be activists: defending the right to read and the right to access information. It is our responsibility to ensure that the stories on library shelves and in archives reflect the whole of the communities that they are supposed to represent. But we also need to be facilitators: it is difficult for an individual person to determine actions that will help in the struggle against book banning. As librarians continue to fight against the tide of book banning, we can teach others to become warriors as well.