by Grace Millet

Native Land Digital, also referred to as simply Native Land, is a digital database and map that contains information about indigenous peoples’ lands throughout the world. Started and led by indigenous activists from around the globe, Native Land does its best to create a comprehensive map of territories that are or once were solely occupied by native peoples.

The mission of Native Land is stated on their “About/Why It Matters” page: “Native Land Digital strives to create and foster conversations about the history of colonialism, Indigenous ways of knowing, and settler-Indigenous relations, through educational resources such as our map and Territory Acknowledgement Guide. We strive to…develop a platform where Indigenous communities can represent themselves and their histories on their own terms. […] Native Land Digital creates spaces where non-Indigenous people can be invited and challenged to learn more about the lands they inhabit, the history of those lands, and how to actively be part of a better future going forward together.” The goal of Native Land is twofold: to provide information to indigenous peoples and to further the understanding of colonialism’s effects on indigenous peoples for non-indigenous individuals who might want to learn more.

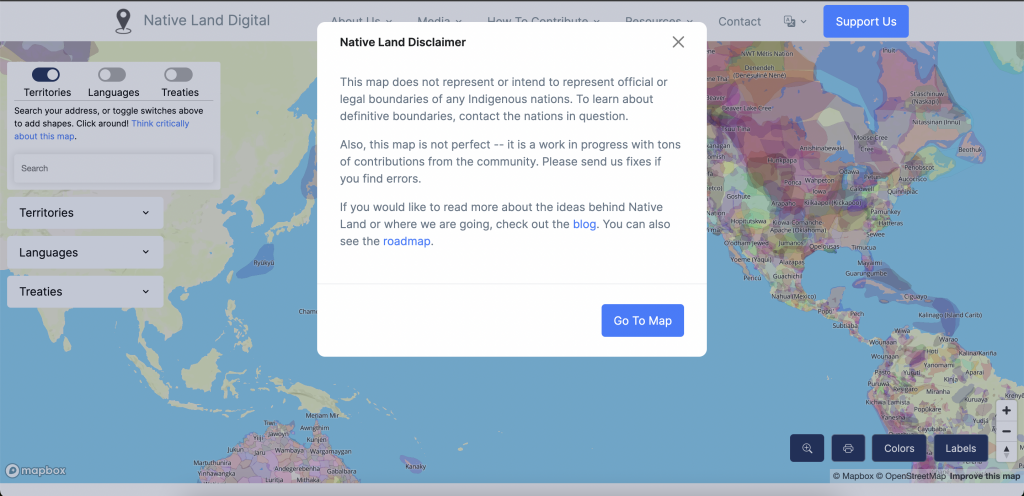

There is an enthusiastic focus on outreach by crowdsourcing information and asking community members for their knowledge as soon as one opens the website. A popup appears, acknowledging that the map beyond it is not perfect and asking for input from those who find discrepancies or errors. This simple statement reaffirms their mission to allow indigenous communities to tell their own stories. There is also an acknowledgement that the land boundaries represented on the map do not necessarily reflect legal territory boundaries at this time—the history of indigenous territories is fraught and deeply complex and cannot simply be presented on a map, interactive or static. Native Land’s effort to document these land boundaries is noble but also humbled by such recognition. The team at work behind the scenes seem driven by their mission statement and understand that they are not working to tell the story on behalf of indigenous peoples; rather, they are working diligently to facilitate the ownership of this history by indigenous peoples themselves. This community-centered outreach is necessary to tell fuller, truer stories about those who may have otherwise been left behind by history and to allow them to more accurately fill in the gaps of the narratives that have already been recorded.

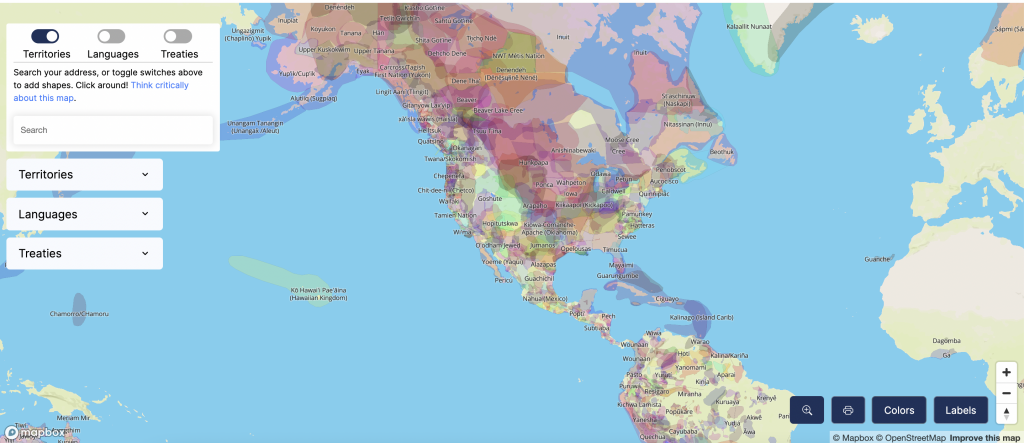

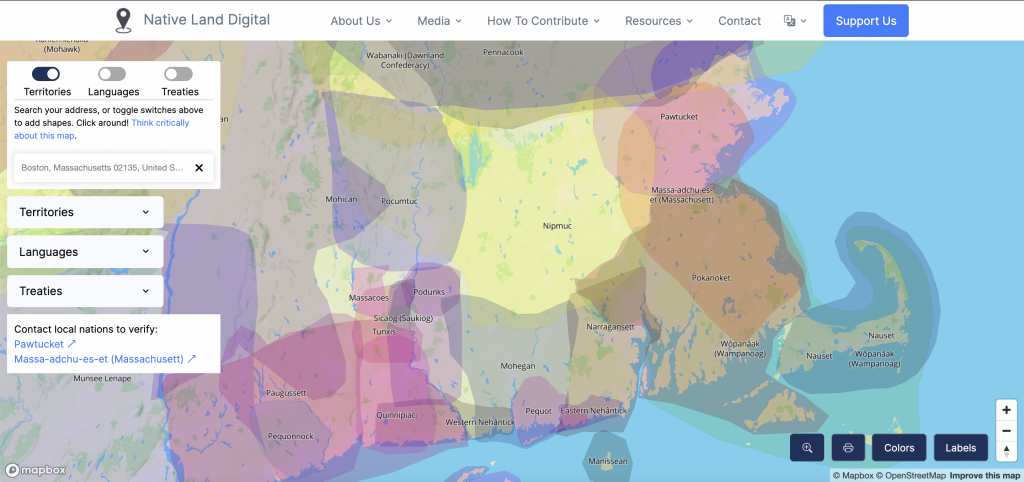

The flagship project of Native Land is the interactive map on their homepage, which documents the entire globe, including arctic and Antarctic land masses. This colorful map that highlights different indigenous territories and their overlapping boundaries allows users to zoom in and out, enter their address for more information about the land their home is on, and, once those territories are clicked, offers information about the tribes and native peoples who once lived there with hyperlinks to current information about these groups. The map is dynamic, and it lets users engage in research that empowers them to continue on to learn more about who used to live where they live, as well as what other tribal lands surround those territories. It begins conversations about indigenous groups in the area that the user might not have been aware of before their search, tribes they had never heard of, or tribal presence that is much more deeply rooted than a user might have thought. And, beyond this revelatory information, Native Land’s map can provide information not just about those indigenous peoples’ histories and current circumstances, but also a way for those who have descended from settlers to attempt to pay personal reparations to the tribes who have an ancestral claim to the land on which the user currently lives and from which they benefit.

I discovered Native Land a few years ago and have used it to look into paying reparations to local indigenous peoples and to learn more about those who used to live where I grew up. Since happening upon the website, I have checked back every year around Thanksgiving and have watched it continue to grow with more information, more colorful territories popping up on the map, and a wider breadth of knowledge about the world outside of North and South America. To my delight, there have been other resources added to the website, such as growing territories, languages, and treaties lists; the expansion of the site into the mobile app environment to facilitate further outreach; and a teacher’s guide to help educators start conversations about colonialism and indigenous peoples’ treatment with their students. These resources consolidate information on the history of indigenous peoples and the effects of colonialism, as well as the sheer magnitude of the diversity between indigenous peoples; they allow users to understand that the phrases “indigenous peoples” or “native peoples” encompass a multitude of different cultures, rather than a single type of individual within a larger cultural group. These resources—especially the mobile app and the teacher’s guide—also allow for easy sharing of this information, whether it be by word of mouth between friends or in a classroom.

Overall, Native Land is an excellent example of a community-focused database for the cultural heritage of many groups that have, since the recent past, not been acknowledged or was thought to have been at risk of historical erasure. With a strong connection to their mission and a leadership composed of indigenous activists and allies, I can see them continuing to grow and updating their resources to keep their users well-informed about the valuable cultures of the peoples they document.

*Please note that all hyperlinks connect to their corresponding pages at native-land.ca and are present for the reader’s convenience.