by Christine Jacobson

In her 1893 short story, “The Fullness of Life,” Edith Wharton described a woman’s nature as a “great house full of rooms”:

“...there is the hall, through which everyone passes in going in and out; the drawing-room, where one receives formal visits; the sitting-room, where the members of the family come and go as they list; but beyond that, far beyond, are other rooms, the handles of whose doors perhaps are never turned; no one knows the way to them, no one knows whither they lead; and in the innermost room, the holy of holies, the soul sits alone and waits for a footstep that never comes.”

This passage stayed with me long after I forgot the outlines of the story. The metaphor is as deft as it is haunting, but it also reveals Wharton’s passion for architecture and design. Before House of Mirth brought Wharton critical acclaim as a novelist, Wharton was an authority on decorating and gardening. Her first book, The Decoration of Houses, was a treatise on the new post-Victorian style of American interiors which eschewed clutter and ornamentation in favor of symmetry, utility, and clean lines. Together with her co-author, Ogden Codman, Wharton ushered in the new reigning style of fine-de-siecle America. In 1901, Codman and Wharton embarked on a new project that would put their principles into practice: The Mount, Wharton’s summer home in the Berkshire Mountains.

The Mount is an autobiographical house. It was designed by Wharton exactly to her tastes with elements borrowed from Italian, French, and English traditions—but the execution is wholly her own. Though it contains 42 rooms, The Mount is considerably smaller than the neighboring “cottages” built by wealthy families, such as the Vanderbilts, who preferred to summer in New England. Also in contrast with her neighbors, Wharton opted for a facade of white stucco and black wooden accents rather than brick or stone. Compared with the dark Richardsonian mansions nearby, The Mount cuts a bright, cheerful figure among the verdant Berkshire hills.

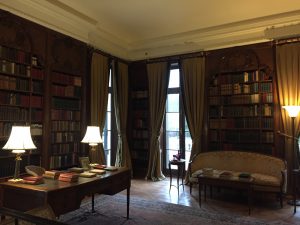

I visited The Mount last April to see writer Lauren Groff in conversation with editor Heidi Pitlor as part of the museum’s True Conversations series. The chat was held in Wharton’s airy drawing room and was filled to capacity. Groff spoke movingly about what it meant to her to be inside Wharton’s home and to have browsed Wharton’s library earlier that day. She put her hand over her heart as she described opening Wharton’s copy of Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre. For me, her story represented three generations of incomparable women writers coming together across space and time through a single book—a book preserved with immense care and kept in a library conserved through great effort and fortitude. For me, this is what great cultural heritage institutes are all about.

The library is one of two crown jewels at The Mount. The other is Wharton’s breathtaking Italianate garden (—Wharton also published a book on Italian Villas and their Gardens in 1904). Each cost the Edith Wharton Restoration organization, which owns the house, roughly two and a half million dollars to restore. Stephanie Copeland, former president of the Restoration  Organization, had hoped the gardens and library would galvanize visitors and fundraising opportunities for the house. By 2008, neither had materialized and the organization defaulted on its loans. Copeland resigned and Susan Wissler stepped in to replace her. The Restoration Organization quickly lurched into advocacy and outreach mode. It launched a Save the Mount campaign which led to an outpouring of donations from the public. Additionally, The Mount targeted a cadre of wealthy donors to join the newly formed National Committee, an annual giving society that would support the operation of the estate. The bar for becoming a member is an annual gift of one thousand dollars, but many members are rumored to have pledged far more. (Francis Ford Coppola and George and Laura Bush are among its members.) By 2015, The Mount was back in the green.

Organization, had hoped the gardens and library would galvanize visitors and fundraising opportunities for the house. By 2008, neither had materialized and the organization defaulted on its loans. Copeland resigned and Susan Wissler stepped in to replace her. The Restoration Organization quickly lurched into advocacy and outreach mode. It launched a Save the Mount campaign which led to an outpouring of donations from the public. Additionally, The Mount targeted a cadre of wealthy donors to join the newly formed National Committee, an annual giving society that would support the operation of the estate. The bar for becoming a member is an annual gift of one thousand dollars, but many members are rumored to have pledged far more. (Francis Ford Coppola and George and Laura Bush are among its members.) By 2015, The Mount was back in the green.

In addition to its fundraising efforts, The Mount also recognized, crucially, its responsibility to the local community and as a result, revitalized its public events program. The True Conversations series I attended last spring is one exciting facet of this in which beloved local figure and nationally acclaimed short story editor Heidi Pitlor interviews American female authors. The museum’s new stewards have also embraced its reputation as a haunted house and host ghost tours in the evenings. And in 2020 the Mount will celebrate the centennial of Wharton’s novel, Age of Innocence with film screenings, discussions, book clubs, and an exhibition. I’m planning to drive out to The Mount to see Elif Batuman in conversation with Jennifer Haytock about the novel, which happens to be one of my favorites, later this year. (If you’re persuading low-income librarians from Boston to rent a zip car to drive four hours for your events, you’re doing something right.)

Wharton only occupied the house for a decade. Though it was one of the most prolific periods of her life as an author, it was also a period of profound suffering and deprivation. Wharton’s husband, Teddy, suffered from a depression that grew worse during their stay in the Berkshires and their life together became intolerable. Wharton sold The Mount after their divorce in  1912. For a house with such a cheerful facade, The Mount has had an unusual share of woe. However, its current stewards appear to be on the right path. Cultural heritage professionals know that advocacy starts with giving people a reason to believe in your work. (See Larry Hackman’s Many Happy Returns for more advocacy wisdom.) With its shrewd grooming of sustainable donors and effective outreach to its local community, The Mount has shown it has plenty of reasons to have our support.

1912. For a house with such a cheerful facade, The Mount has had an unusual share of woe. However, its current stewards appear to be on the right path. Cultural heritage professionals know that advocacy starts with giving people a reason to believe in your work. (See Larry Hackman’s Many Happy Returns for more advocacy wisdom.) With its shrewd grooming of sustainable donors and effective outreach to its local community, The Mount has shown it has plenty of reasons to have our support.