In this latest edition of Unbound’s InfoFuture-inspired series on library-based artist residencies, we’ll be taking a look at a successful example of an artist-in-residence program at an innovative public library system.

In 2013, the Madison Public Library in Madison, Wisconsin launched the Bubbler, a maker-focused program active in all branch locations and in various outreach locations. Their vision for the Bubbler is to foster creativity in their community through activities, demonstrations, and workshops focused on art, design, and technology.

In 2013, the Madison Public Library in Madison, Wisconsin launched the Bubbler, a maker-focused program active in all branch locations and in various outreach locations. Their vision for the Bubbler is to foster creativity in their community through activities, demonstrations, and workshops focused on art, design, and technology.

In September of that year, the Bubbler launched an artist-in-residence program. Their residencies are both brief and frequent. Each is one to three months long, and as soon as one residency ends, the next begins. The Bubbler’s artist residencies are very successful at engaging with the library’s surrounding community. Their artists have taken quite varied approaches that illustrate different types of impact a resident artist can make.

In September of that year, the Bubbler launched an artist-in-residence program. Their residencies are both brief and frequent. Each is one to three months long, and as soon as one residency ends, the next begins. The Bubbler’s artist residencies are very successful at engaging with the library’s surrounding community. Their artists have taken quite varied approaches that illustrate different types of impact a resident artist can make.

The Bubbler’s artists are encouraged to pursue work that is accessible to the whole community. A public library’s demographic pool is about as broad as it gets, so this can prove challenging. In the Dream Collectors’ residency, they accomplished it by engaging with a subject that everyone can relate to: sleeping and dreaming. During all open library hours, the Bubbler operated a space where children and adults could create art based on recent dreams they’ve had, and display them in the space. This very wide range of hours made it easier to reach patrons on all sorts of schedules. The Dream Collectors also undertook several special events for patrons, including a late night cocktail party in the library and a two-hour workshop on Surrealist games.

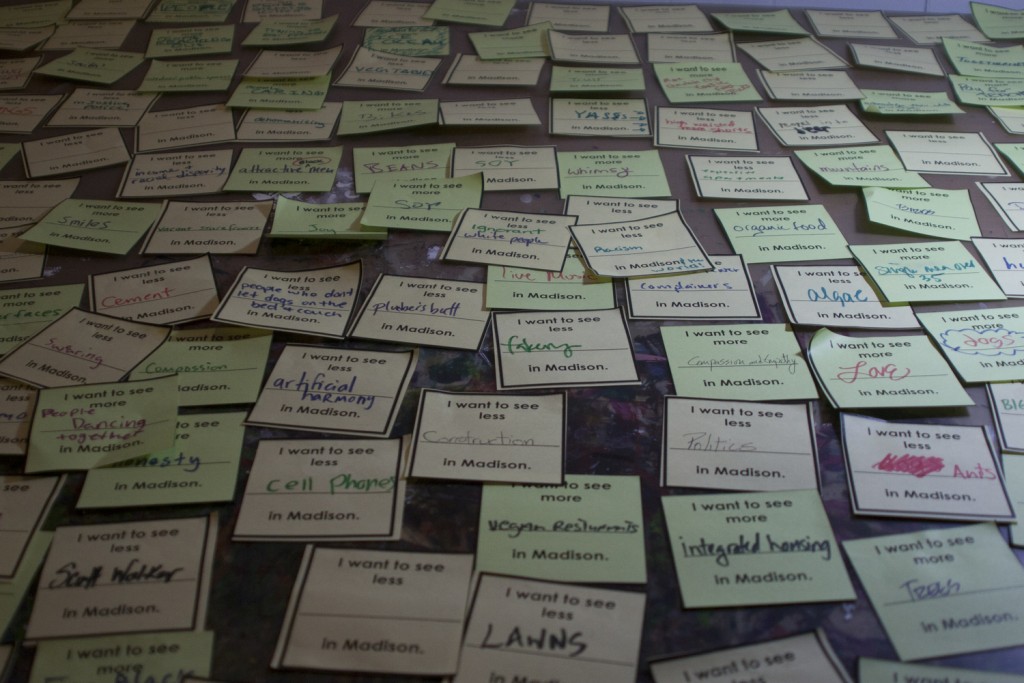

Other residencies have engaged with community-specific subject matter. The Private Public collective’s residency, titled Our Madison, “invite[s] residents to participate in visualizing and recording our current lived experiences (both positive and negative) within our city to foster conversations about the issues facing our community.” The results included a wall of sticky notes with community members’ desires for the future of the city, as well as a map of the city that patrons marked at places they’ve had important experiences. At the end of the residency the artists published a book of the results, titled People’s Atlas: Our Madison. The collective’s focus on the lives and surroundings of the library’s patrons helped them connect and create meaningful collaborative art.

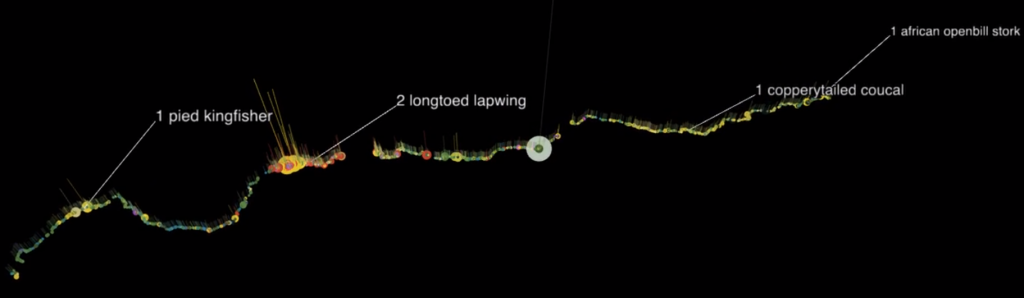

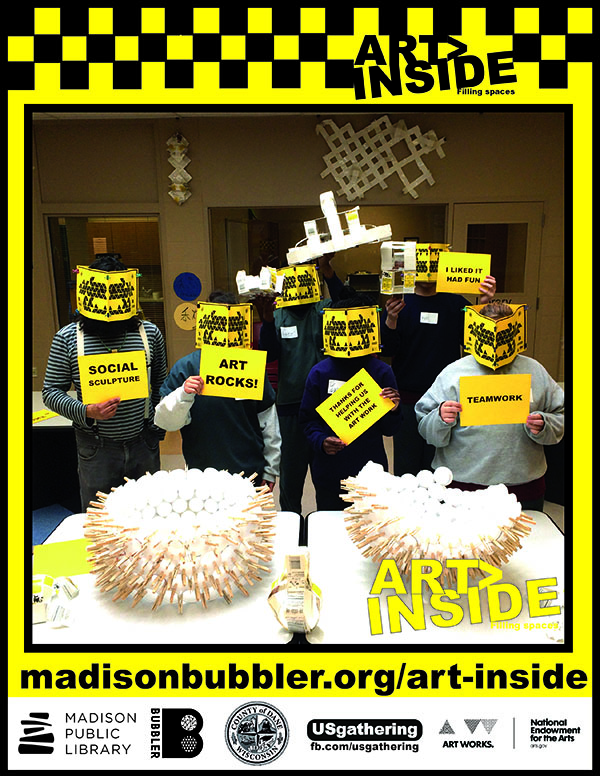

Victor Castro’s residency was noteworthy for his work with marginalized community members and for his ecologically conscious use of the community’s recycled materials. One initiative from his residency, the social sculpture project ARTinside: filling spaces took place at the Dane County Juvenile Detention Center. He teamed up with the teens residing there to create sculptures out of recycled materials like clothespins and milk cartons. They then installed the sculptures in the detention’s common spaces. During these sessions, everyone wore special masks they’d assembled and used nicknames they’d chosen for themselves. The project gave the participants space to play with their identity and agency to decorate the parts of the center they spent the most time in. During a radio appearance discussing the project, Castro summed up his goals: “We are filling the spaces of the facility but also, why not, we are trying to fill up spaces inside them, inside the souls and the minds of these kids.” In the end, the project generated a great deal of enthusiasm from both the teen participants and the detention center’s staff.

An artist in residence at a public library faces the challenge of engaging a patron base that is extremely broad and diverse. Through their attention to relevant and accessible subject matter, community engagement, and thoughtful connections with marginalized groups, the Bubbler’s artists have provided a great model for other public libraries looking to initiate similar programs.

The Bubbler’s rapid success brought the library new funding opportunities. In 2014, the Madison Public Library, in partnership with the University of Wisconsin-Madison, received a two-year National Leadership Grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services to help support the Bubbler and its many initiatives, including their artist-in-residence program.

For more information on The Bubbler’s artist-in-residence program and a list of artists who’ve participated, check out their website!

(Post by Derek Murphy)