The question of whether we still need libraries continues to be raised in various forums, from the New York Times (da Loba, 2012) to Forbes (Denning, 2015) and NPR (Weeks, 2015), to personal and community blogs. Those who question the library’s value tend to point to the—seemingly—ubiquitous access to information in the digital age. Why do we need libraries when we can find almost any information instantaneously online? Responses to this question are often couched in terms of bridging the digital divide and providing access to computers and the internet for those who do not have (and perhaps cannot afford) it at home, or providing access to higher-end technology and multimedia production tools, as in the case of makerspaces. While these arguments are legitimate, they (and the questions that prompt them) ignore the basic fact that in our knowledge economy, information is treated as a commodity—an entity which has economic value and can be owned, bought, and sold. As such, vast quantities of information are not freely available, regardless of access to technology. This issue of information as a commodity has important consequences for society and for libraries, and it is crucial for librarians to engage with the issue as professionals and as citizens in a democratic society. In this blog post, I would like to consider some of the implications of the commodification of information in the hopes of spurring further conversation on the topic.

Our market orientation, the idea that we are treating more things as commodities and more organizations as businesses, is evidenced in the information professions by our increasing use of business terminology—referring to patrons as “information consumers” and discussing marketing and branding of our institutions and services. Although living in an information/knowledge economy highlights the issue, the idea of commodifying information is not a new one. Traue (1997) traces the shift in orientation from information as a public good to a consumer product. He begins with the invention of the printing press, which helped to separate information—a packaged product—from knowledge—an internalized understanding. Once information was separate it could be owned, and copyright laws were developed to help protect that ownership and promote creation of new products. Later, Shannon and Weaver introduced their theory of communication that introduced the possibility of quantifying information into discrete units, which allows then for buying and selling. Traue also touches on certain government policies, including those of President Reagan, which moved the production of certain government information into private hands, thereby increasing the cost of access.

Advances in technology have added another layer of complexity. On the one hand, technology has made the tools for producing and disseminating information more widely available, meaning more people can participate in the process of creating and sharing information. Further, the Internet, Web, wireless technologies, and mobile devices have increased the ability to access information from almost anywhere at any time. While it would be reasonable to assume that these changes have led to an abundance of information that is easily and freely accessible, the reality is more complicated. In fact, while information itself is more abundant than ever before, access is often limited. In many cases, publishers and other copyright holders appear to be exploiting the uncertainties arising from new technologies to exercise even greater control over the information they produce. For example, many of the major publishing houses and vendors such as EBSCO currently engage in a model whereby libraries cannot buy materials like books or journal subscriptions, but pay licensing fees in order to access information for a limited time, after which they must pay for continued access or lose the content (Bessner, 2002). Similarly, several of the largest book publishers refuse to license ebook titles to libraries, or impose artificial limitations, such as automatically removing a title after a certain number of circulations (Maier, 2014). Another approach is the “pay per” model, in which individuals are charged for access to single resources. For example, a Google search for the topic “commodification of information” will result in several scholarly articles. In many cases, only the abstract of the article is freely available online. If the reader wishes to access the entire article, they are prompted to pay as much as $40 for a single article. In many cases, these same readers could request the article for free through interlibrary loan at their local library, but that option is not displayed on the result screen, and many people do not realize this option exists. These pricing models can lead to decreased access for both libraries and users.

In addition to impacting whether and how users access information, the commodification of information can also influence what gets created and published, since publishers only want to invest in material that will sell. Similarly, grant makers and foundations might not fund research in unpopular areas. In terms of scholarly communication, Lawson, Sanders, and Smith (2015) suggest that, as a result of this marketing orientation, certain research questions and topics will become marginalized as researchers choose not to pursue areas for which they cannot secure funding or which are not likely to get published. In an interview for Inside Higher Ed, Hans Radder suggests that this economic focus could lead to bad science, as scientific researchers are influenced by the pharmaceutical companies and other industries that fund their research. Further, he notes that “commodified research tends to focus on short-term economic gain, while a significant social function of academic research has always been to provide a more general “knowledge infrastructure” that can be drawn upon when confronted with novel future challenges” (Jaschik, 2010). Commercial publications likewise are driven by market forces. Indeed, some critics suggest that the lack of diverse literary characters, especially in children’s books, is due in large part to the perception that there isn’t a large enough market to promote such books (We Need Diverse Books, n.d.). As a result, whole communities of people cannot see themselves reflected in the books they read.

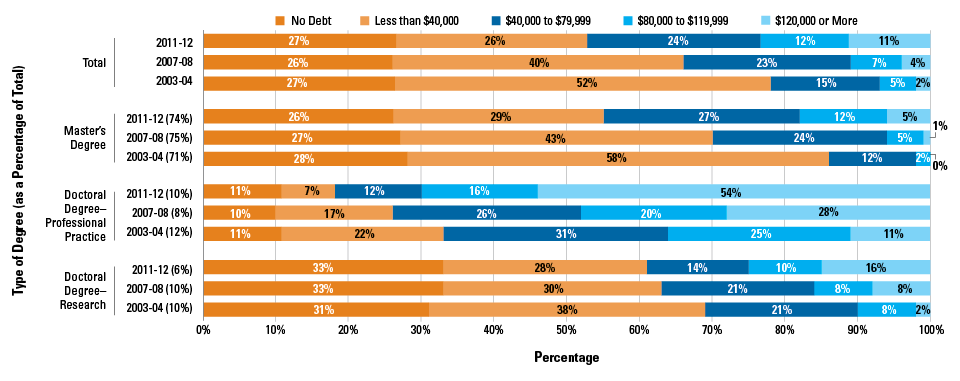

Access to quality information is a necessity. People need information to inform decision making from who to vote for in elections, to what to eat in order to be healthy, to which products are the best use of their money. In fact, it has been argued that access to information, though not codified in the United States Constitution or Bill of Rights, is actually a human right that underpins all other human rights (Bishop, 2011; Weeramantry, 1995). Thus, creating barriers to the access of information becomes a social justice issue, as “access to information, as well as the requisite education and skills necessary to participate effectively under current economic conditions is heavily influenced by social class” (Adair, 2010). This inequality has to do with more than just access to technology such as computers, smartphones and internet in order to access information, but also has to do with access to education and ability to pay for information sources and services. Further, this inequality impacts not just individuals but communities, institutions, and even whole nations who may not have the technological infrastructure to access or the financial capital to pay for information. For instance, Lawson, Sanders, and Smith (2015) raise concerns about the production and dissemination of scholarly information, including the rising subscription costs of academic journals, which limit access to those who cannot afford such prices and effectively “provide a privileged and stratified access to this scholarly information and knowledge” (p. 2). Further, they note that in many cases the research being reported in these articles and journals was funded by government and taxpayer money, begging the question of why the general public is not able to freely access information when they provided the money to enable its creation.

Given that the basic mission of libraries is to provide free and equitable access to information, the commodification of information raises both challenges and opportunities for librarians. To begin with, librarians have a role to play in helping to raise awareness of and promote use of open access publications (Lawson, Sanders, & Smith, 2015). While traditional publishing models charge the end user—whether it be individuals, libraries, or other entities—to access the information they produce, open access resources make their publications available to users for free. While open access journals have gained some popularity, especially in the sciences, some scholars and critics still question their quality and refuse to publish with them. Librarians can help scholars and researchers to understand the value of open access, highlighting that fact that articles in open access journals tend to reach a wider audience and get cited more frequently, and helping them to understand that many open access journals are peer-reviewed just like traditionally published journals, so the quality of research should be comparable. Librarians can also help these scholars and researchers learn about which copyrights they retain when publishing, and whether they can deposit copies of traditionally published articles in open access repositories.

Librarians also have a role to play in helping patrons develop critical information literacy skills. As noted above, many different interests influence publishing, which can lead to the spread of “bad science,” propaganda, and other misinformation. Unfortunately, once it is digested, poor information can be difficult to correct and can lead to misunderstandings and poor decision-making. As professionals skilled in assessing the authority and credibility and at researching sources, librarians can help users develop an informed skepticism, questioning material and digging deeper into sources in order to evaluate them before forming opinions or making decisions based on that information. Through formal education programs, tutorials and self-paced guides to resources, or one-on-one instruction on an as-needed basis, librarians can work with patrons to develop the competencies needed to evaluate and use information effectively.

Finally, librarians should raise awareness about the impacts of information commodification, and the role of the library with regard to this issue. In fact, I would suggest that the debate around whether we need libraries could be reframed around the issue of commodification of information—in a knowledge society, information has economic value. As such, it is not, nor is it ever likely to be, entirely free. Therefore, libraries are necessary to continue serving their original purpose of helping to provide free and equitable access to information in all formats. It is important for people to understand that vast quantities of information are not freely accessible, even with sophisticated technology and high-speed online access, and to consider how limitations on access affect participation in a democratic society. Public libraries in the United States, though funded by taxpayer money and operating within a local government structure, have a mission that requires them to act independently of these external influences, effectively creating what Habermas termed a “public sphere” where citizens can access information and debate topics (Webster, 1995). In an economic system where information has value and can be owned, bought, sold, access to the information necessary for everyday life decision making and participation in a democracy is limited to those who can afford it, libraries can help to bridge the gap and make information more widely accessible. By not engaging with this issue, librarians are potentially undercutting that role and the value that they bring to their communities.

Adair, S. (2010). The commodification of information and social inequality. Critical Sociology, 36(2): 243-263.

Bessner, H. (2002). Commodification of culture harms creators. American Library Association. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/offices/oitp/publications/infocommons0204/besser

Bishop, C.A. (2011). Access to Information as a Human Right (Law and Society). El Paso, TX: LFB Scholarly Publishing LLC.

da Loba, A. (2012). Do we still need libraries? New York Times: Opinions. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2012/12/27/do-we-still-need-libraries

Denning, S. (2015, April 28). Do we still need libraries? Forbes. Retrieved from http://www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2015/04/28/do-we-need-libraries/

Jaschik, S. (2010, October 25). Commodification of academic research. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2010/10/25/radder

Lawson, S., Sanders, K., & Smith, L. (2015). Commodification of the information profession: A critique of higher education under neo-liberalism. JLSC 3(1): ep1182. http://jlsc-pub.org/jlsc/vol3/iss1/1/

Maier, R. C. (2014). Big Five Publishers and Library Lending. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/transforminglibraries/sites/ala.org.transforminglibraries/files/content/BigFiveEbookTerms091314.pdf

Traue, J.E. (1997). The commodification of information. New Zealand Studies. Retrieved from http://ojs.victoria.ac.nz/jnzs/article/viewFile/390/313

Webster, F. (1995). Theories of the Information Society. Chapter 6 “Information Management and Manipulation: Jurgen Habermas and the Concept of the Public Sphere. New York, NY: Routledge.

We Need Diverse Books. (n.d.). Press kit. Retrieved from http://weneeddiversebooks.org/press-kit/

Weeks, L. (2015, May 5). Do we really need libraries? NPR History Department. Retrieved from http://www.npr.org/sections/npr-history-dept/2015/05/05/403529103/do-we-really-need-libraries

Weeramantry, C.G. (1995). Access to information: A new human right. The right to know. Asian Yearbook of International Law, 4 (1995): 102.

This post was written by SLIS Assistant Professor Laura Saunders.