by Toben Traver

What happens when we engage students in the process of historic documentation and research? This is the question that drives the annual Vermont History Day (VHD) program and competition. Since 1983, VHD, administered by the …

Featuring profiles of outreach & advocacy in cultural heritage

by Toben Traver

What happens when we engage students in the process of historic documentation and research? This is the question that drives the annual Vermont History Day (VHD) program and competition. Since 1983, VHD, administered by the …

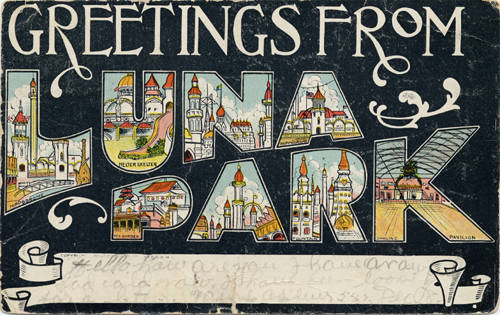

Postcard from the Postcards of Cleveland Collection, part of the Cleveland Memory Project. Credit: Michael Schwartz Library, Cleveland State University.

by Jessica Chapel

When Bill Barrow was a child growing up in Cleveland, an electric sign on the city’s …