Using a digital library as a platform in which anyone can build tools and services is now a hot topic in the library and information science field. Libraries can maximize use of their digital collections — and fulfill their mission of democratizing access to knowledge – by providing a reliable method for developers, researchers, and others to integrate library data into applications, visualizations, and tools. Digital libraries not only offer access to materials, but the ability to create tools and products also. This new approach stands in contrast to the standard web portal, which provides access to digital collections through a site’s search and browse functionality. In his September 2012 Library Journal article, technologist David Weinberger writes:

One aim of this switch [to libraries as platforms] is to think of a library not as a portal we go through on occasion, but as infrastructure that is as ubiquitous and persistent as the streets and sidewalks of a town, or the classrooms and yards of a university. Think of the library as co-extensive with the geographic area it serves, like a canopy, or as we say these days, like a cloud.

The Digital Public Library of America (DPLA) feels strongly about the promise of platform architecture. DPLA is a free online library that provides access to millions of books, photographs, maps, audiovisual materials, and other resources from libraries, archives, and museums across the United States. The DPLA provides access by way of metadata aggregation for millions of records and thumbnails from our national network of partners, often referred to as hubs. We bring the hubs’ metadata into the DPLA platform and enrich it with added data, like geolocation coordinates, allowing us to populate items on a map, among other innovative pieces of functionality. The aggregated metadata is distributed for free and unrestricted use under a Creative Commons Public Domain dedication, a formal method for labeling items in the public domain. Developers access DPLA metadata through a tool called an application programming interface (API), which feeds user-defined information to an external application, like a smartphone app or a visualization. (Alternatively, for those interested in unmediated access to the platform, we also offer bulk download of all, or subsets of, DPLA’s metadata database.) Since our launch in April 2013, our app library has grown to hold 18 different types of DPLA-powered applications.

The “library as a platform” concept is powerful, especially when you consider how the same data powering massive digital libraries, like DPLA and Europeana, can be used to create novel interfaces, ones often built for different purposes than its original architects envisioned. The front-end DPLA website is one DPLA interface, not the only DPLA interface.

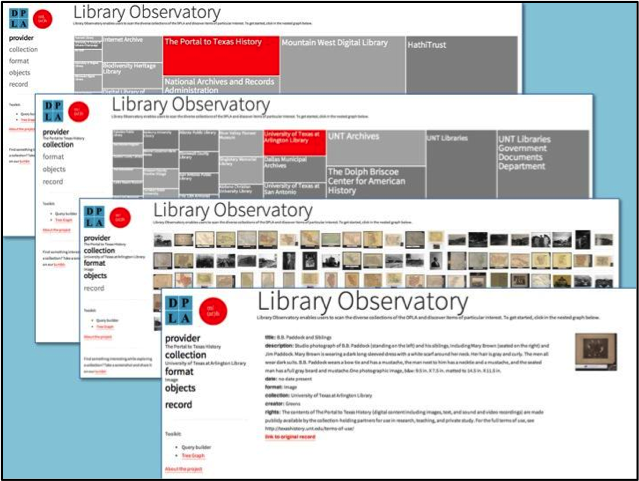

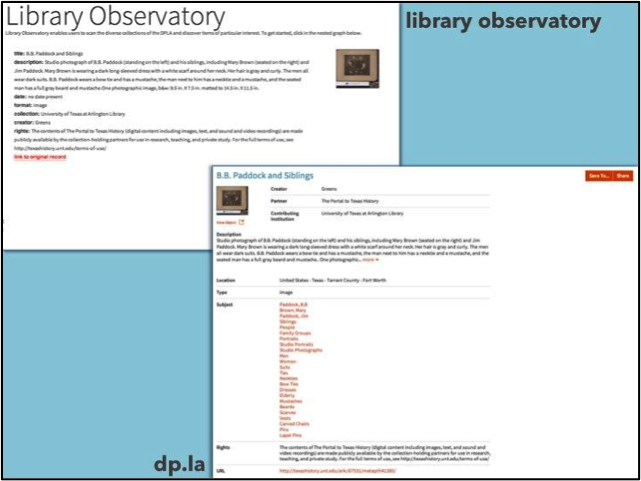

For instance, Library Observatory, built by Harvard’s metaLAB using the DPLA platform, allows users to search DPLA through a nested, interactive graph that visualizes all of our collections by relative size, format, and type of object. Users can browse DPLA’s repository by clicking through dynamic representations of our various collections, a feature not available through the DPLA-designed front-end (see Figures 1 and 2 below). Others have built iOS applications that use a phone’s geolocation to create contextually relevant images (OpenPics), visual search tools that allow users to create collections of their favorite items (Culture Collage), as well as many other inventive uses of DPLA’s metadata platform.

Most importantly, the platform model creates a new community of library users, one that may have had little interest in libraries prior to finding the model. The allure of free and open data can attract creative ideas from places beyond the orbit of traditional library communities, expanding the reach of library resources and services. Weinberger writes, “[Libraries as platforms] focuses our attention away from the provisioning of resources to the foment those resources engender. A library as platform would give rise to messy, rich networks of people and ideas, continuously sparked and maintained by the library’s resources.” The rich networks of people and ideas have propelled DPLA’s efforts from day one.

For libraries and archives to continue to create and nurture communities of knowledge and civic engagement, it is essential they provide access to their resources, or portions of their resources, in ways that align with new definitions of “use” in a digital environment.

To join the community of developers building DPLA-powered apps, see our easy-to-read documentation and ideas and projects hub, or subscribe to our tech mailing list. The DPLA App Library contains apps built on our platform. DPLA’s code can be found on GitHub.

(Fig. 2) A side-by-side comparison of the same record displayed on Library Observatory and dp.la. platform, allows users to search DPLA’s collection by way of a colorized tree graph, something unavailable on the DPLA-designed website.

By Kenny Whitebloom, Project Coordinator, Digital Public Library of America (DPLA)