Through its Code of Ethics, Bill of Rights, and Freedom to Read Statement, the American Library Association is clear in its support of intellectual freedom and resistance to censorship. Libraries are heralded as institutions that promote equality and democracy by providing free access to information sources and technologies, as well as instruction in how to access, evaluate, and use these resources. Information is essential to good decision-making and full participation in a democratic society, and ALA (1989) suggests that information literacy, or the ability to access and use information efficiently and effectively, can help to reduce socio-economic disparities. We can point to many examples of librarians standing up for equal access and fighting against censorship, from Miss Ruth Brown who worked against segregation to Ann Sparanese who touched off a campaign that saved Michael Moore’s book Stupid White Men, to the many librarians who spoke out against the USA Patriot Act. While we can certainly be proud of these instances, in reality the history and current situation of libraries is more complex and fraught than these examples suggest.

To begin with, the profession’s commitment to intellectual freedom and equal access is a relatively new development, and there are plenty of examples of librarians during the World Wars and McCarthy eras promoting government propaganda, engaging in censorship, and denying access to entire communities of people. Even now, some librarians contend that as a profession we should be neutral, avoiding taking positions on political and social issues. These librarians often pit the value of intellectual freedom against social responsibility, arguing that if librarians take a stand on social issues, they will inevitably be favoring one perspective and effectively censoring another. However, this argument ignores an important reality: libraries, like any other institution, operate within an existing political and social power structure. Indeed—since libraries deal directly with information—if we accept the adage that information is power, we could argue that libraries need be especially aware of these power structures. Libraries employ systems that were developed by and largely reflect the white, middle-class, Christian, heteronormative culture in which they are embedded. These values and perspectives are evident in our cataloging and classification systems, collections, programming, displays, and so on. By ignoring this reality, libraries are denying the impact of these legacies and are perpetuating the status quo. As such, many librarians challenge the idea of a neutral profession.

The importance of these debates to the field is evidenced by recent conference themes, publications, and even informal conversations on social media. Brian Mathews posted a series of interviews on his blog The Ubiquitous Librarian focused on issues of critical information literacy, social justice advocacy, and challenging the status quo. Library Juice Press publishes monographs on library and information science from a critical perspective. Recent titles have included Information Agitation: Library and Information Skills in Social Justice Movements and Beyond edited by Melissa Morrone and Information Literacy and Social Justice: Radical Theory and Praxis edited by Shana Higgins and Lua Gregory. Librarians on Twitter have regular conversations on integrating critical theory into their practice using the hashtag #critlib, while others have been discussing how to address social justice themes within the new Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) Information Literacy Frameworks.

The Association for Library and Information Science Educators (ALISE) has likewise demonstrated interest in addressing questions of social justice and advocacy. The theme of the association’s 2015 conference was “Mirrors and Windows: Reflections on Social Justice and Re-Imaging LIS Education,” while the theme for the upcoming 2016 conference is “Radical Change: Inclusion and Innovation.” These themes certainly suggest an interest on the part of LIS faculty to integrate a critical perspective into LIS curricula, ostensibly with the intention of encouraging a similar perspective in their students’ professional practice. Certainly, educators like Nicole Cooke at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champagne, Kevin Rioux at St. John’s University in New York, and Emily Drabinski at Pratt School of Library and Information Science, among others, teach courses that focus on social justice, advocacy, and questions of race, gender, and sexual identity in library practices, programs and services. However, such topics are often addressed in separate, stand-alone courses, such as UIUC’s Race, Gender and Information Technology course, or Simmons’ own Information Services for Diverse Users. It is difficult to determine how widespread the attention to these topics is in core MSLIS courses and programs. Yet, without specific attention to these issues, we are at risk of perpetuating exclusionary systems and practices.

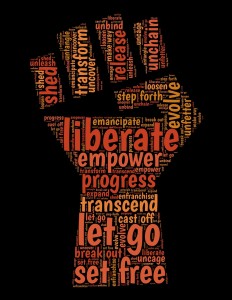

In spring 2016, the SLIS community will be able to engage with these questions and challenges in a special topics course, Radical Librarianship. Beginning with the premise that the library profession is not and cannot be neutral, this course will use a critical theory lens to examine and question the systems, services, and resources employed by our profession. Drawing on the writings of Freire, Habermas, Giroux, and others, we will reflect on the library’s sometimes uncomfortable relationship with race, gender, sexual orientation and identity in order to develop responses that are inclusive of the many communities that we serve. We will examine libraries as socio-political institutions that have the opportunity to be progressive or to promote the status quo, and analyze their role as civic spaces with the potential to foster civic engagement and debate. We will investigate the ways in which libraries promote and silence different voices, include and exclude various communities, and promote and inhibit access.

There is much to be proud of in the history of libraries, and much to be excited about as we engage our communities and develop our programs and services. But if we hope truly to embrace our potential, we first must acknowledge and engage with what is problematic in our profession. After all, we can’t wage an effective revolution unless we know what we are working to change. With Radical Librarianship, we can help to move the discussion forward. I hope you’ll join me!

While there is a limit to how much we can do in a single semester, I’m eager to hear your thoughts and ideas on what you think this course should be! Please see the draft course outline at: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1IIeg3C48Ua6_Qvnv4Bn88YEVU1jMoHw9xxMdv1596Fk/edit?usp=sharing

The Simmons community can comment directly to the document. Others can email me at laura.saunders (at) simmons.edu to share your comments with me.

Presidential Committee on Information Literacy. (1989). Final Report. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/publications/whitepapers/presidential

This post was written by SLIS Assistant Professor Laura Saunders.