In the 2012 science fiction film Robot & Frank, a near-future public library is entirely staffed by just one librarian… and one robot. The robot, named Mr. Darcy, mans the circulation desk, shelves books, and answers reference questions. The librarian handles occasional administrative work. The main character, a patron old enough to remember the way libraries used to be, laments that the human touch has left the building.

This concern has been around for decades. Will machines replace librarians, leaving many unemployed? Will libraries become totally automated? Will robotics alienate librarians from their patrons? Unbound has surveyed the current state of the art in library robotics and found little cause for alarm. In public libraries, academic libraries, and museums, it seems that robots are bringing people closer together, not driving them apart.

In public libraries, robots are now being used as a teaching tool. The Chicago Public Library recently partnered with Google Chicago to provide five hundred Finch Robots for checkout and in-house use. The Finch was designed by Carnegie Mellon’s CREATE lab for usage in computer science education. The robots feature a robust set of input mechanisms, such as accelerometers and light, temperature, and obstacle sensors. They can output complex behaviors, including motion, light, sound, and drawing. These capabilities allow programming beginners to see immediate, tangible results from their work, making the learning process more intrinsically motivating and making abstract concepts more concrete. The robots support a variety of programming languages, from simple visual ones for grades K-2 to professional-level languages like Python and Javascript. The Finches are available to any adult patron, and can be checked out in packs of five to facilitate classroom use. The library’s Northtown branch runs the Code Phreaks programming club for grades 5-12 where members learn how to program the Finch and develop their own uses for them.

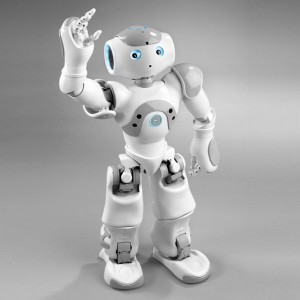

Connecticut’s Westport Library has undertaken a similar robotics project, but on a different scale. Instead of five hundred simpler robots, they’ve acquired two enormously complex ones. The humanoid child-sized robots, named “Nancy” and “Vincent,” are part of French robotics company Aldebaran’s NAO line. The NAOs are equipped with video cameras, directional microphones, tactile sensors, Wi-Fi connectivity, sonar rangefinders, and a complex range of motion. With these input methods available, the robots can be programmed to exhibit complex behaviors. Examples include turning their heads to look at people who are speaking to them, identifying and manipulating objects, and pulling information from the internet to add to a conversation. Nancy and Vincent are charismatic machines, and they attract patrons into the library to see what they’re capable of. Like CPL’s Finch programs, the Westport Library holds training sessions where they teach patrons how to program the NAOs. They hold a series of classes of increasing complexity, Levels One through Three. Those who have completed at least the Level One class are invited to a weekly Open Lab, where attendees can work on their own original NAO coding projects, with assistance from a professional developer. They also hold weekly “Robot Viewing” sessions where they show off some of the behaviors that have been developed thus far – including a “Thriller” dance.

In academic libraries, robotics technology is being used to ease space constraints and make materials more readily accessible. The University of Technology, Sydney (UTS) has recently installed an enormous automated storage and retrieval system (called the Library Retrieval System, or, LRS) underneath its library. UTS’s system takes the form of six enormous robotic cranes that tend to thousands of closely packed bins of books. When a patron requests a stored book from the online catalog, the LRS automatically springs into action. One of the cranes retrieves the appropriate bin and brings it to an employee, who retrieves the requested book. The book is then delivered to the library’s hold shelf, where the patron can pick it up. The entire process generally takes about fifteen minutes. The LRS allows for extremely dense storage of books, obviating the need for an expensive and unwieldy off-campus storage facility and freeing up space in the library for new student-centered services like collaborative study spaces, maker spaces, and multimedia editing stations.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uaSormCA1K8

The LRS naturally raises questions about discoverability – if everything is packed into metal boxes underground, then how will students stumble upon works they didn’t know they were looking for? The library has taken steps to mitigate this problem. The collection’s most commonly used materials are still shelved out in the open for students to browse. Additionally, the UTS libraries have added new features to their online catalog to enhance discoverability. Their “collection ribbon” is an intuitive visual way to narrow search results, and their “shelf view” feature displays books as they would appear on the shelf, surrounded by the books they would have been shelved with. They intend to add recommendation-related features in the future. By quietly and efficiently freeing up space, the LRS seems primed to create new opportunities for human-to-human interaction in the library.

Museums are currently exploring robotics in their capacity to improve accessibility. The de Young Fine Arts Museum in San Francisco recently acquired a pair of telepresence robots. These machines open up the gallery floor to patrons with disabilities that would otherwise prevent them from visiting in person. The robots, called BeamPros, are almost like mobile Skype avatars. A patron can reserve a Beam tour in advance, log into the robot from their computer at home, and then pilot it around the museum. The BeamPro is a 5’2 tall frame on wheels, holding up a screen, a microphone, speakers, and a camera. A live video feed of the patron’s face is displayed on the screen, and the camera picks up high-resolution video of the space for the pilot. A second camera points down toward the ground, allowing the pilot to avoid obstacles.

The BeamPro is fully mobile and under the full control of the pilot. Unlike a prerecorded video tour or interactive website, the BeamPro grants its user agency and physical presence. A person piloting a BeamPro can move about the space as they wish, and linger on a particular work of art as long as they like. They can interact with other museum patrons and with employees. Henry Evans, an advocate for and user of this technology, has this to say: “In five years, I would like to see museums all around the world at least experimenting with this technology, and in 10 years for it to be ubiquitous. It will be the next great ‘democratization of culture.’” Currently, Suitable Technologies, the developers of the BeamPro, are partnering with five museums around the country to pilot this remarkable use for their product. CBS News covered one of these partnerships in this video news report.

Despite the often-dire predictions of science fiction, in today’s landscape robots seem to be a largely beneficial presence in libraries and museums. Whether they’re used for education, organization, or accessibility, these machines are facilitating human connections, not eroding them. If we continue on the path we’re on, then Robot & Frank‘s Mr. Darcy will not be diminishing the library’s human touch any time soon.

Have you had any experience with robotics in a library, museum, or archive setting? Let us know about it in the comments!

(Post by Derek Murphy)