In social psychology, the contact hypothesis of prejudice reduction holds that sustained personal interaction with members of a group can decrease negative feelings and prejudice toward that group. Following this principle, a recent development in public and academic libraries has made a marked difference in divided communities.

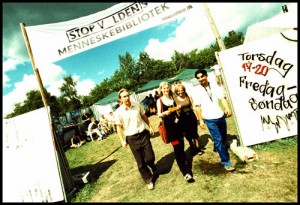

Beginning at an anti-violence festival in Copenhagen in 2000, the Human Library has taken on a life of its own, with events held at public and academic libraries, festivals, and conferences in every continent. At a Human Library event, it’s not books or media that are on loan, it’s people. Patrons, or “Readers”, at the library can check out “Human Books”, volunteers who represent a marginalized group or who have a unique story to tell. Typically, Readers are presented with a list of Books and allowed to choose whom they’d like to check out. When a Reader checks out a Book, the two individuals sit down for a conversation. Readers are able to ask the Book the questions they’ve always wondered but been too afraid to ask. Often Readers are encouraged to ask about common stereotypes related to the Book. For example, those who are misinformed about Islam and harbor negative views towards Muslims could speak with a Muslim Book and have their prejudices weakened through friendly, compassionate discourse.

Potentially rocky conversations like this need to happen in the right kind of venue, to minimize the potential for conflict and foster positive interactions. Libraries are a natural fit. As community learning centers, they promote a spirit of inquiry and discovery. They are calm, quiet, and comfortable. People are used to keeping interactions calm and low-key in a library. Libraries are widely recognized as a safe space.

I recently spoke with Rosanne Rosella, Adult Program Coordinator at the Henrietta Public Library (HPL), about a Human Library program they conducted in September of this year. Lately the HPL has been experimenting with new types of programming including running pop-up libraries around town. They’re currently planning to build a little free library. Running a Human Library program fit right in with these initiatives.

Their first challenge was seeking out volunteers to serve as Human Books. They first made a list of potential demographics their Books could represent. They considered the dynamics of their local community when brainstorming ideas. Rochester has the nation’s largest deaf population per capita, so they sought to include a deaf person in their program. They contacted high profile community members (like Arun Gandhi, non-violence activist and grandson of Mohandas Gandhi), people who’d broken new ground in the community (like a black woman who’d served as the first woman patrol officer in Rochester’s police force), and people whose personal lives intersect with political controversy (like a married gay couple living in Rochester). Some of their Books came to them unbidden—one employee asked if she could represent people with learning disabilities in the program. They interviewed their potential Books to ensure that they’d fit the goals of the program and would be able to carry on potentially difficult conversations with strangers in an amiable way.

The event was a success. Attendance was good for a mid-sized community library. The demographics of the attendees were in line with the general demographics of their other programs’ attendees: mostly young seniors around their early 60’s. There were a few younger couples and a family with teenagers as well. Many of the Readers were regular program attendees, but there was also a surprising boost in attendance thanks to the efforts of the Books. One Book advertised the event at her church, and a lot of her fellow churchgoers came to see her at the library. The Readers in attendance were very positive about the experience. The Books had enjoyed the experience as well, and some of them were very moved by it. The previously-mentioned gay couple remarked that they were surprised at how deep the Readers’ questions were, and said they’d been changed by the experience. Rosella hopes that Readers had their minds changed in positive ways from the interactions the program had fostered.

Rosella would love to run a Human Library program again. She feels that about eighteen months would be a good buffer period between Human Library programs, so that it’s a fresh and surprising experience every time. For librarians looking to run their own Human Library programs, she recommends that special attention be paid to the logistics of connecting Readers with Books. Typically Readers are given a set period of time to converse with a Book, to ensure that the Book is able to speak with every interested Reader during the program. It can be difficult to organize the transitions from Reader to Reader, as keeping the timing straight for all of the Books at once can be daunting. Rosella recommends having an individual volunteer assigned to each Book, if possible, to help keep things running smoothly. Before running a Human Library program, it’s a good idea to contact the Copenhagen-based Human Library Organization. They provide free support to all Human Library events in the form of print training materials, web publicity, and more.

Human Library programs aren’t just bringing community members together, they’re also bringing organizations together. The HPL’s program was not the first Human Library event in Rochester, NY; the Rochester Public Library had previously teamed up with the University of Rochester’s libraries to run a successful event this past January. This partnership is an excellent example of how public and academic libraries can collaborate to better serve both of their patron pools. Their collaboration didn’t stop with their first program either. They’re now planning on teaming up to create a catalog of all Human Books who have made appearances in Rochester to date, to facilitate in running future Human Library Programs. The University of Rochester produced this lovely video of one of their past Human Library Programs:

You’ve probably been there at some point in your life: You’ve met someone whose lived experience is completely different to yours. You want to learn more about them, but you worry that your questions might come off as uninformed, gauche, or flat-out offensive. Usually these questions go unasked, but now librarians have the power to create safe spaces for this kind of dialog, and in this way help to stamp out prejudice in our communities.

(Post by Derek Murphy)