You are teaching a college history course and you want to make copies of an essay for your students, but you don’t have the rights to it. You’re a rap musician and you want to sample an old jazz song, but you can’t find any definitive proof of who owns the rights to it, so you can’t ask permission. You’re a filmmaker working on a horror movie about a cult, and you want to use copyrighted historical footage of the Jonestown cult in your film. In each of these cases, Fair Use could save you from major legal consequences.

Fair use is a doctrine of copyright law that allows one to use portions of a copyrighted work that one does not own the rights to without legal consequences. Without Fair Use, derivative works including parody, satire, educational excerpts, and more would be subject to legal consequences.

This past week was Fair Use Week, an annual celebration to spread awareness of Fair Use and to advocate for its continued strength. As our contribution to the cause, we here at Unbound would like to walk you through a hypothetical example of how Fair Use can be beneficial, from two different perspectives: education and the arts.

This past week was Fair Use Week, an annual celebration to spread awareness of Fair Use and to advocate for its continued strength. As our contribution to the cause, we here at Unbound would like to walk you through a hypothetical example of how Fair Use can be beneficial, from two different perspectives: education and the arts.

Let’s say a filmmaker is working on a documentary about media representations of the city of Sarasota, Florida. Across the street, a college professor is teaching a class about Sarasota’s history. Both of them acquire a copy of “White Sandy Beaches,” a short video commissioned by the Sarasota County government in 1953 to promote tourism. The filmmaker would like to use a clip from the video in her film, in order to comment on its factually inaccurate depiction of the city’s beaches. The history professor would like to show her class this video, as it includes unique footage of an important speech by a former mayor of Sarasota.

The history professor has used footage like this before in class, and knows that she doesn’t have to worry about rights issues when displaying it in the classroom. However, this semester she would like to include the full video as part of the students’ out-of-class studies, and have it streaming online for them. She visits the university library and speaks with the librarian in charge of digitization.

The librarian decides to consult the ARL Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for Academic and Research Libraries (PDF link). The first section, “Supporting Teaching and Learning with Access to Library Materials via Digital Technologies”, lays out both the requirements and the ideal procedures for making course material available online. Normally, it would be illegal to stream a copyrighted work online, but there are several factors that make it possible to do so legally in this case through Fair Use. This video was originally intended as television advertising for a city, to draw in tourists. Taking that video and placing it into an educational context transforms its usage such that the librarian would not be impinging on its original purpose. It is being viewed on an online instructional technology platform instead of television, and it is being used to teach students history rather than to advertise. These differences in context and usage make this work a good fit for fair use. If the librarian were digitizing a work that was originally created for academic educational purposes, then this usage would be a bit sketchier, as it would not significantly change the context or purpose of the work. If that were the case, it would be best to use only an excerpt.

Though this video is a good fit for educational fair use, there are still best practices to use when making it available. It’s important that only enrolled students, and faculty/staff working in an educational capacity have access to the digitized video (this can be legally problematic when teaching MOOCs, as any member of the public can enroll and access the work). The video needs to be available only over the course of the semester the class is being taught in. Students accessing the video should be presented with a full scholarly attribution, and a paragraph explaining the students’ rights and responsibility when accessing the material under Fair Use. With these measures in place, there will be no legal trouble with streaming the video.

The documentary filmmaker has a much greater challenge in store for her, as she is not creating this work in a non-profit capacity or as part of an educational institution. If she is taken to court by the rights holder of “White Sandy Beaches,” then she will not have an air-tight defense in the same way our academic librarian would. In the domain of the arts, Fair Use can be fairly subjective, and rulings can be based in large part on the whim of a case’s judge. Fair Use is codified into law as a series of guidelines, not hard rules. The four factors that are considered in a Fair Use case are as follows:

- The purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes

- The nature of the copyrighted work

- The amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole

- The effect of the use upon the potential market for, or value of, the copyrighted work

The filmmaker’s best bet would be to first find the copyright holder of the video and ask for permission to use it. If she can officially license an excerpt of the video for her film, the she will not have to worry about Fair Use in the first place. In many cases this is untenable for financial reasons. In our case, the filmmaker simply cannot identify the current rights holder. She attempted to seek out the film’s copyright record using the US Copyright Office’s web search but was unable to find it. Due to their relative obscurity and short lifespan of use, ephemeral promotional videos like this one can often pose a challenge when tracking down the owner. It’s quite possible that the creators never filed an officially documented copyright claim on this film in the first place. Even so, they still own the copyright and can bring a legal challenge in the case of infringement.

In a world without Fair Use, this would be the end of the line for the filmmaker. Without any way to get permission from the rights holder, any usage of material from “White Sandy Beaches” would leave her open to a lawsuit for copyright infringement. She would have to make do without the excerpt, and her future audience would not have the chance to appreciate these rare images of the past from a city that is rarely filmed.

Luckily, her usage of this video does arguably fall under the realm of Fair Use, and there is a path she can take to safely show clips from it in her film. The Documentary Filmmakers’ Statement of Best Practices in Fair Use (PDF link) specifically discusses situations like this. If a filmmaker is “employing copyrighted material as the object of social, political, or cultural critique,” then such usage generally constitutes Fair Use. In the same way that an essay about a play would need to be able to quote that play, a film discussing another film must be able to quote that film. Because the filmmaker in our example is critiquing media representations of Sarasota, it is legally permissible for her to show clips of those media representations as part of that critique.

The one critical point to consider in this usage is this: the filmmaker’s use of “White Sandy Beaches” must not damage the original work’s market value by taking its place. In order to minimize the chance of that happening, the filmmaker would be best off using only portions of “White Sandy Beaches” and not the entire film. She would need to ensure that the footage is used for a different effect than the source material was originally intended for. As her documentary will be about media representation and not about selling Sarasota to tourists, the filmmaker does not have to worry about taking over the original film’s market share. The two films will occupy very different places on the market. A Fair Use defense never guarantees a win in court due to Fair Use’s openness to interpretation, but this is certainly a strong enough case that the filmmaker could feel confident with moving forward.

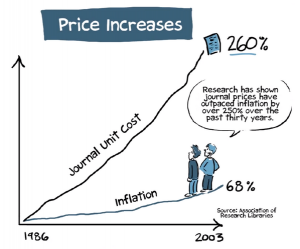

Through the careful application of Fair Use best practices, both librarians and artists are able to educate and entertain in ways that would otherwise be illegal. Because Fair Use is determined on a case-by-case basis, best practices are constantly evolving as court decisions create new precedents. New innovations in technology and communications have created possibilities for media appropriation that were unimaginable in 1976 when Fair Use was first codified: fanfiction, fan art, YouTube supercuts, music mash-ups, and so many other internet-based artworks are driving the law to keep up. MOOCs, which can accommodate many thousands of students from across the world, are pushing the boundaries of what Fair Use will allow. With luck and with strong advocacy, we’ll keep the protections we have, and see Fair Use expand to cover these new cases, keeping innovation in education and the arts possible.

The New York Public Library explains how Fair Use helps them accomplish education and preservation goals.

(Post by Derek Murphy)