Why libraries are helping their users create

As the world goes digital, some are questioning the future of libraries. If you think of a library as only a storehouse of books, you might wonder: who will need libraries when most of our reading is available digitally, on a computer, or on mobile devices?

When you think about the reason libraries have become storehouses of books, and think about the underlying reasons why libraries exist, you end up with a mission statement like the one proposed by R. David Lankes: “The Mission of Librarians Is to Improve Society through Facilitating Knowledge Creation in Their Communities.” That’s the reason people needed books, and still need information (in any format) — to facilitate their own knowledge creation activities.

Libraries maintain relevancy by offering programs and services that help users create content — services, such as helping local authors write books, offering co-working spaces, and helping people make interesting objects using 3D printing. This is an expansion of the roles libraries have already been involved in for some time, such as offering public computing, assistance with job searching, and serving as community gathering places. Library users have long valued these services, as described in the Pew Internet report, “How Americans Value Public Libraries in Their Communities.”

Best mobile apps for creative projects

Since libraries are getting involved in different ways with helping their users create, it’s good for librarians to know some of the best mobile apps to recommend to users as tools for their creative projects. Below is a sample of the many apps available that can be used for content creation and curation. Apps for working with photos, video, art, and music, may be the topic of a future post.

For those who want an easy way to start creating interactive books

● Book Creator for iPad – Android, iOS. An easy-to-use app for creating multi-media ebooks, which include text, images, video, music, and narration. Great for working with kids.

● iBooks Author – Mac OS. Although it is not a mobile app (it runs on Macs), iBooks Author enables you to create interactive ebooks for Apple’s iBookstore with multimedia features for viewing on iPads. It’s easy-to-learn, easy-to-use, and free. Some libraries are using it to create interactive ebooks from special collections. For example, see the New York Public Library’s NYPL Point: John Cage’s Prepared Piano.

For people who want to make non-boring presentations

● Keynote – iOS. An easy-to-use presentation app similar to PowerPoint that enables users to design beautiful presentations. It comes with a set of well-designed themes. Pro themes are available from several publishers as well.

● Slideshark – iOS. Present PowerPoint slides on your iPad.

● Haiku Deck – iOS (iPad only). Create presentations with an elegant, minimalist look. One unique and useful feature of Haiku Deck is its ability to search Creative Commons-licensed images to use in your slides.

● Prezi– iOS. Create presentations on a zooming, virtual canvas. People either love or hate Prezi.

For those who want to use shared whiteboards for demonstrations and teaching

● Explain Everything – Android, iOS (iPad only). Create screencasts or live demos of annotated documents, drawings, photos, or videos on your iPad.

● Doceri – iOS (iPad only). Another popular and useful interactive whiteboard app.

For those who want to create designs for 3D printing

● 123D Design – iOS (iPad only). Autodesk makes several apps in this area. 123D Design is a good place to start. Designs can be initiated on an iPad, saved in the cloud, and finished on the desktop with 123D Design for Mac or Windows.

● Makies Doll Factory – iOS (iPad only). Build fully-customizable digital dolls. See “Libby, the librarian.”

● Blokify 3D Printing & Modeling – iOS. 3D modeling software that enables kids to create toys they can play with virtually or physically via 3D printing.

● Thingiverse – Android, iOS. Share and browse user-created digital design files for 3D printing.

For those who want to curate and share content on the web

● Flipboard – Android, iOS. A visual news reading app that provides an appealing way to browse, read, and share stories from a variety of sources. Use it to create “magazines” on topics of your choice. Here’s an example: “Book as App – Interactive, Multi-Touch.”

● Scoop.it – Android, iOS. Collect stories on a topic to share via a “magazine” on the web.

● Paper.li – iOS. A curation app for the creation of virtual newspapers on specific topics.

Additional information about what libraries are doing to facilitate content creation in their communities

Batykefer, Erinn, Laura Damon-Moore, and Christina Jones. “Library as Incubator Project.” A site that advocates for libraries as incubators of the arts.

Chant, Ian. “Opening Up: Next Steps for MOOCs and Libraries.” Library Journal. Discusses an academic library offering its own MOOCs and a public library using a MOOC as the foundation of a summer reading program. Makes the case that libraries are well-placed to be part of experiments with MOOCs.

Farkas, Meredith. “Libraries as Publishers: Our Push to Change the Publishing Landscape.” American Libraries. Exploring the role of libraries in enabling publishing, through publishing the work of the library’s constituencies (public libraries), and through publishing open-access work (academic libraries).

“Four Local Libraries Honored for Offering Cutting-edge Services.” Digital Book World. ALA honored four libraries offering cutting-edge technology services, including services for easy video creation by faculty and students, and using Instagram’s API to capture photos tagged with the library’s hashtag and display them online and in the library.

Godin, Seth. “The future of the Library.” Seth Godin’s blog. Describes librarians as people who can bring domain knowledge and access to information, helping users create and invent.

Morozov, Evgeny. “Making It: Pick up a Spot Welder and Join the Revolution.” The New Yorker. Essay about the “maker movement,” its history, and where it could go.

Nawotka, Edward. “A Visit to BiblioTech: The 21st Century All-Digital Library.” Publishing Perspectives. The story of an all-digital public library in San Antonio, Texas. They loan out e-readers for home use. Discusses how economical it was to build, compared to other public libraries with print collections.

Peterson, Andrea. “Need to use a 3-D printer? Try your local library.” The Washington Post. A story on library 3D printing services, focusing on the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Library in Washington, D.C.

Peterson, Andrea. “Digital age is forcing libraries to change.” Washington Post. . All about the “digital commons” at the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Library in Washington, D.C. Try out e-book readers, use a 3D printer, use the Skype station, a co-working space, and more.

Rendon, Frankie. “The Changing Landscape for Libraries & Librarians in the Digital Age.” TeachThought. Discusses why libraries are more relevant than ever, with librarians offering digital services, technology training, and serving as key partners in community relations.

Resnick, Brian. “The Library of the Future is Here.” Business Insider. Describes libraries not as warehouses of books, but as services and tools for the commons.

Sipley, Gina. “Surprise! It’s the Golden Age of Libraries.” PolicyMic. On re-imagining the library as digital space, with books no longer the focal point.

Stinson, Susan. “Writers in residence at Forbes Library: Three Programs.” Library as Incubator Project. Local writer describes her experience as writer-in-residence at Forbes Library in Northampton, Massachusetts.

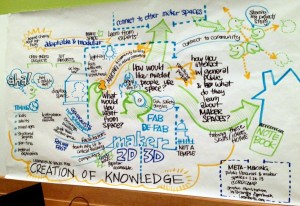

“Symposium: Creative making for libraries & museums.” Dysart & Jones. http://www.creativemaking.org/. A symposium held in July 2013 that focused on creative making in libraries and museums, with examples of makerspaces, fab labs, and more.

Tennant, Roy. “The Mission of Librarians is to Empower.” The Digital Shift. Many of the ways we empower our users and communities — increasing knowledge, providing access to tools, and more.

All of these apps and many more are discussed in my forthcoming book, Apps for Librarians: Using the Best Mobile Technology to Educate, Create, and Engage. Libraries Unlimited, Fall 2014. Sign up for my newsletter, “Mobile Apps News,” and receive useful tips twice a month, and a notification when the book is released.

All of these apps and many more are discussed in my forthcoming book, Apps for Librarians: Using the Best Mobile Technology to Educate, Create, and Engage. Libraries Unlimited, Fall 2014. Sign up for my newsletter, “Mobile Apps News,” and receive useful tips twice a month, and a notification when the book is released.

By Nicole Hennig ’82LS