Design Thinking and Doing Design, part 1

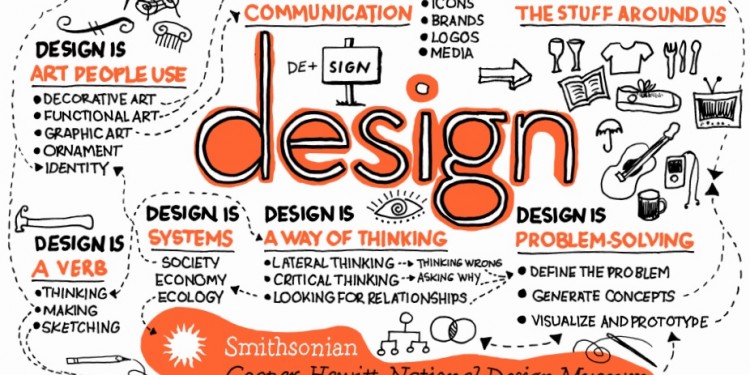

Design Thinking. Backward Design. Accessibility. SAMR. Universal Design for Learning (UDL). These days, in discussions of the future of librarianship, pedagogy or education in general, there are so many terms and acronyms thrown around but what do they all mean? Many of these terms are borrowed from engineering, urban planning, and design, to name a few. Are people in the library and information sciences field using them properly? You also may read those terms and think, “These don’t belong together!” I’m here to make the claim that they do and that they should be studied together in order to be the most successful. “What MAKES a Library” is a series of articles for UNBOUND in which I will define these terms and explore how these concepts are being put into action in libraries while showing where the intersections of these ideas can be ways to utilize them in library spaces. This article’s focus is on design thinking.

Before I go any further, allow me to introduce myself as the 2016-2017 Dean’s Fellow for SLIS Initiatives and your resident UNBOUND blogger. Just this fall, I began my quest to earn my Dual Degree Masters in Archives/History aka goodbye social life, hello manuscripts. I fulfill many librarian stereotypes; for example, I have a cat (named Gabriel, Gabe for short), I went to an all women’s college (Anassa Kata Bryn Mawr), I’m listening to classical music as I write this and I absolutely love to read. When you hear the word, “librarian”, I’m willing to bet (unless you are a past or current MLIS student) that an image of an old, crotchety grey-haired lady with a tight bun and cat-eyed glasses whisper-yelling “Shhhh!” comes to mind.

Am I right? Thought so.

In case you didn’t get the memo, librarians and libraries are SO much more than that. I won’t waste time writing about what’s already been written time and time again that libraries are the future and they are spaces of learning, community gathering, and innovation. But hopefully, this series will give you a slice of the many creative ways libraries and librarians are constantly remaking themselves in the 21st century. Links to related readings are available at the end of this post.

To be quite frank, I didn’t know the definition or origin of “design thinking” until quite recently. I had never even heard the term before I began my fellowship this semester. A Google search returns a lot of entries about Tim Brown, current CEO of IDEO, but his first major publication using the terminology of design thinking was in 2008, but I had a hunch it had deeper roots. In true history student fashion, I researched where the term came from to bring context to how it is being deployed in libraries today.

Brief History of Design Thinking

The concept was born in England and the United States during the early to mid-1960s in the field of engineering. Design thinking was an extension of the idea that design engineering should be more human centered and perhaps, design even deserved to be recognized as its own complex knowledge field. The first usage of the term occurs in Leonard Bruce Archer’s book, Systematic Method for Designers published in 1965: “Ways have to be found to incorporate knowledge of ergonomics, cybernetics, marketing, and management science into design thinking.” Archer is lobbying to make the science of design an interdisciplinary subject and most, if not all, of his fellow academic contemporaries agreed with him. Design thinking remained in the sciences, design engineering, architecture and urban planning fields until David Kelley interpreted its principles for business purposes in the early 1990s. In the late 1970s, Kelley studied under Professor Robert McKim, one of two creators of the Joint Program in Design at Stanford University and Kelley soon taught at Stanford himself. The program was multidisciplinary and illustrates the collaborative nature of design thinking. Simultaneously, Kelley began his own design firm, and after a few reorganizations, it is now IDEO. Around the same time in 1983, Steve Jobs employed Kelley’s firm to help design the first Apple mouse. They remained close friends and collaborators until Jobs’ death in 2011. Kelley served as CEO of IDEO until 2000, when Tim Brown became CEO. Kelley is still chairman and a managing partner of the global firm.

Key Components

Through my research and conversations with designers, I’ve identified some key components of design thinking that possibly distinguish it from other problem-solving approaches:

- Harness optimism. When posed with a challenge, a design thinker must believe that there is at least one better solution out there than the pre-existing alternatives.

- Empathy is also key when approaching a problem through the design-thinking lens. How can you solve another person or community’s problem without seeing it from their point of view?

- No bad ideas. No thoughts are considered ‘bad’ or ‘stupid’; rather it becomes something to expand upon and dig further into, instead of tossing it to the side.

- Comfortable Environment. In order for the above components to work, design thinking must take place in a space that fosters creativity, enthusiasm, and collaboration. In academia, or life in general, people tend to very hard on themselves and are afraid of appearing ignorant to others. I know I am. Creating a comfortable environment might be one of the hardest tasks of design thinking because it involves trust and risk. It requires that you change your perception of what’s considered ‘good’ and ‘bad’. The people in a room “doing design thinking” need to support one another through this process.

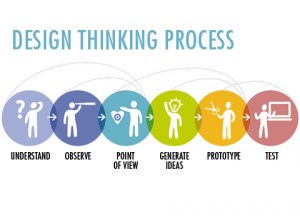

Visualizing Design Thinking

In the spirit of practicing UDL or Universal Design (which you’ll read about later on in this series!), I’ve included a visual representation of the process of design thinking. The three major thinking spaces of the process are: Inspiration, Ideation and Iteration. These are referred to as spaces because they are not necessarily concrete steps that only happen once in a set order. Rather, it’s an approach and a mindset and these are guidelines for how to reach the end goal: a product that solves a problem. Plus I got to make GIFs, so that was fun.

Design Thinking in New Spaces

Design Thinking in New Spaces

Design thinking didn’t leave the designer bubble until around 2011. However, in the early to mid-2000s there were writings by designers about how this mindset could rescue America from its K-12 education crisis, re: the achievement gap. There were those in the design and business worlds practicing design thinking for decades and it’s unclear why the education sector didn’t follow suit.* I suspect fear had a lot to do with it. The process of design thinking is not linear; it does not follow a prescribed order of steps. In fact, it’s cyclical so going through the process once does not necessarily mean it’s over. Tim Brown even says that to those experiencing it for the first time, it can feel chaotic. By human nature, chaos and the unknown is terrifying, we fall back on what is comfortable and familiar. In K-12 environments, the prospect of purposely causing disruption to established processes could definitely evoke feelings of caution and maybe even danger. Another major component of the design thinking framework is that those living the problem tend to be part of the team that innovates and collaborates to find a solution. For example, students would need to be involved in redesigning the summer reading lists or rearranging the physical layout of the cafeteria. Placing the students in a position of power and agency could erase the authoritative teacher, submissive student dichotomy. I think back to an English class in high school where we were assigned to write 3 potential college essays and the teacher would then choose which one we should perfect and edit at least 10 (I’m not kidding) times. The teacher would give out Ds to “inspire” you to work harder. At the end of it all, I absolutely hated my topic and my teacher. I even hated writing. Involving the people you’re serving in a syllabus design, room re-design, program planning, etc. has extreme potential to make for a much better learning or user experience for everyone involved.

Sometime between 2010 and 2011, educators started to jump on the design thinking bandwagon. IDEO partnered with an independent school in New York to tailor the framework for an educational context and published the Design Thinking for Educators toolkit and workbook in 2011 and the second edition came out in 2013. Now, I acknowledge there is a ton more to be written about the convergence of design thinking and education but my ultimate focus here is libraries. Although, I think of librarians as invaluable educators and libraries as vital spaces for learning, so it strikes me as odd that it took until 2014 for libraries to join the design thinking world. I have a feeling that the fear of the unknown and a step away from traditional problem-solving might have been a factor in the delay in libraries embracing design thinking. Especially in our fast-paced, technocentric world where people are still asking, “Are libraries relevant?!”, I can completely understand why librarians were hesitant. In 2014, the library world did get their own IDEO toolkit, which was actually a result of a project sponsored by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The Chicago Public Libraries and Denmark’s Aarhus Public Libraries secured this funding together. This partnership represents the innate nature of teamwork in librarianship, which is yet another reason that it is strange libraries weren’t pulled into the design thinking camp until quite recently.

Speaking of partnerships, a recent team of designers and librarians participated in a Library Test Kitchen this summer 2016 at Simmons SLIS. Upon hearing about this course and reading some news articles about the Library Test Kitchen, I got the impression that it was taking MLIS students on a previously untraveled academic path; that offering design thinking to librarians was very new and unprecedented. I believed it, but I wanted to know why it was so brand new and this is why I tracked the history of design thinking, both for my own understanding and for yours, the readers. To provide concrete evidence that employing the design thinking as a structured approach to solving problems in libraries is indeed in its infancy. It was the first iteration of the course to be offered to MLIS students and I had the opportunity to speak to some of the instructors and students about their experiences. Plus, a video of the whole LTK@Simmons experience is in the works. Stay tuned for that article and video!

*As an aside, I constrained my research to when the field of education and libraries actually used the term “design thinking” in news articles and literature because I do not doubt that there were places prior to 2010 that used a similar framework but simply didn’t refer to it as ‘design thinking’.

Recommended Reading

Further reading about the future of libraries:

- UNBOUND Link Round-Up

- InfoFuture

- Transforming Libraries into Learning Labs

- http://www.infodocket.com/category/news/

- “Libraries as Hubs for 21st Century Learning” article

- The Future of Futures | Designing the Future

Further reading about design thinking:

“Design thinking” as it’s known today might be new to libraries, but I’d argue that librarians have always been designers and that librarianship is actually a design profession, not a social science field.

Oh, wait, I already did argue that! http://hdl.handle.net/1773/37159

🙂

Hi Rachel,

Thanks for reading my post and linking to your work! I agree, “design thinking” isn’t some revolutionary way of thinking but I’ll write more about this in my next piece! 🙂

– Elizabeth

Looking forward to reading it!

Really nice article! Thank you for sharing!

Impressive post. I really enjoyed this.

Want more from simmons blog.

Testing.pk NTS, ETEA, PPSC Test Apply Online Roll Number Slips Answer Key Result

Testing.pk NTS, ETEA, PPSC Test Apply Online Roll Number Slips Answer Key Result