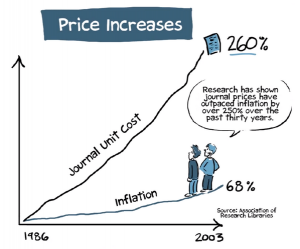

Student loan debt has fast become a major economic factor in the 21st century US. The percentage of students taking on debt and the average amount of debt have both increased dramatically in the past twenty years. The specter of student loan debt looms large in students’ minds, and can have a major influence on their career choices. Library and Information Science as a field is not immune to this.

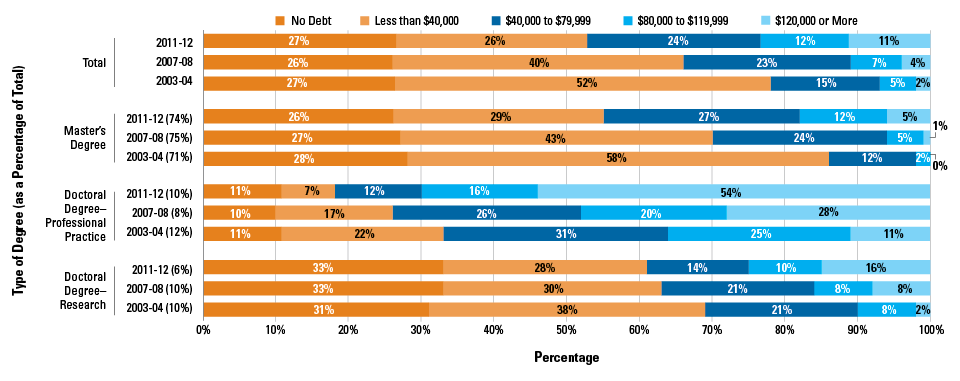

In 2012, 74% of Master’s degree recipients had taken on student loan debt. The median debt of graduate borrowers was $57,600. For comparison, librarians’ median yearly income that same year was $55, 370. When the cost of an MLIS degree is higher than a librarian’s yearly income, it can present a problem for prospective MLIS students. A student considering pursuing an MLIS degree may opt against it to avoid a punishing debt load, preferring to remain in a paraprofessional position or dedicate themselves to another field entirely. Students who do decide to attain the degree may, upon graduation, find themselves unemployed, underemployed, or simply not earning enough to cover their monthly loan payments.

Students have always faced challenges related to the price of master’s degrees, but the fast increase in cost of both undergraduate and graduate education has amplified these problems to a never-before-seen level. The long-term effects on our profession may be significant. If the cost of education continues to rise, we risk creating barriers to entry for MLIS students of a lower socioeconomic status, leading to a field that self-selects for only those candidates who can afford to pay. This would have a deleterious effect on diversity in the field. We also risk alienating talented students who might opt to seek a different degree that will remunerate them enough to pay back their debts. Additionally, if potential MLIS students opt to remain in paraprofessional positions en masse, then we risk the MLIS degree falling from prominence.

These are extremely difficult problems to solve, but there are, thankfully, a few valves for releasing the pressure on MLIS graduates. We’ll focus on one in particular: student loan forgiveness plans. The federal government has reacted to the fast growth in student loan burdens by instituting programs to help graduates have their monthly payments lowered and their debts forgiven. These programs tend to be aimed at helping graduates who are entering public service positions. Luckily for us, librarians are included under that umbrella.

These programs have an unfortunate tendency toward unnecessary complexity and obscurity, so in this post I’ll explain the one that has the greatest potential to help MLIS graduates: Public Service Loan Forgiveness (also known as PSLF). To put it simply, PSLF allows you to greatly reduce your monthly loan payments, but still repay the loan in the same time span as a normal repayment plan (ten years).

Who is Eligible?

Any person working at least 30 hours per week in public service can use PSLF. This includes those working a single full-time job as well as those working multiple part-time jobs, as long as the total number of hours worked is at least 30. A public service position, for the purpose of PSLF, is defined as “any employment with a federal, state, or local government agency, entity, or organization or a not-for-profit organization that has been designated as tax-exempt by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC).” Any librarians or archivists working full-time at a public library, public university, private non-profit university (almost all private universities are non-profit), public school library, non-profit private school library, non-profit archive, or non-profit organization are eligible. Almost any librarian, archivist, or other information professional job works with PSLF, as long as it’s not at a for-profit company.

It’s very important to remember that not all loans work with PSLF; only Federal Direct Loans are eligible. FFEL and Perkins loans are not eligible, but they can be consolidated into Federal Consolidation Loans, which can then be used with PSLF.

How does it work?

PSLF allows you to forgive the entire remaining balance of your loan after making 120 monthly payments (the equivalent of 10 years), while meeting the eligibility requirements detailed above (basically, working full-time in the public sector). You may see this and ask, “wait, after ten years of payments shouldn’t my loans be paid off normally anyway?” This is true, the standard loan repayment plan does set your payments so that your loan is fully repaid after ten years. The reason that PSLF works is that you can combine it with a repayment plan that shrinks your monthly payments. This way, you can make much smaller payments per month, but still have the loan paid off in the same amount of time. Because the remaining balance will be forgiven, you will have potentially put far less money into repaying the loan than you would if you’d paid it in full.

There are three repayment plans you can use while pursuing PSLF:

Income Based Repayment Plan: Your payments per month are capped at 15% of your discretionary income if you borrowed before 7/1/2014, or 10% of your discretionary income if you borrowed after 7/1/2014.

Pay As You Earn Plan: Your payments per month are capped at 10% of your discretionary income.

Income Contingent Repayment Plan: Your payments per month are capped at either:

-20% of your discretionary income, or

– what you would pay on a repayment plan with a fixed payment over the course of 12 years, adjusted according to your income.

Each of these plans has different requirements you must fit to be eligible. When combined with PSLF, then it is, of course, best to use whichever of the three reduces your payments the most. Most librarians will be eligible for either Income Based Repayment or Pay as You Earn, depending on when you took out your loans. Check the links to each plan I included above for more information on whether you’re eligible for them.

An example case:

Finaid.org has a very helpful Income-Based Repayment Calculator, which we’ll use to crunch some numbers. We’ll use the numbers from the statistics at the beginning of this article. If you have loans from before 7/1/2014, and you switch your repayment plan to Income Based Repayment, then your loan payments will be capped at 15% of your monthly income. Our example borrower is a single librarian living in MA, earning $55,370 per year and carrying $57,600 in Direct Unsubsidized loan debt with a 6% interest rate. We’ll use the 2014 median income growth rate, 1.58%, to project his potential growth in income over the next ten years as he’s making payments. According to the Repayment Calculator, if our hero uses 15% Income Based Repayment combined with Public Service Loan Forgiveness, then after 10 years his loans will be forgiven and he will have paid $60,404.43 in total. Under a standard repayment plan, he would have paid $76,737.29 in total. By using IBR and PSLF, he will have saved $16,332.86.

The previous example used median numbers, but your own particular situation will have its own unique characteristics. If you’re making less than average for a librarian, or you have a particularly high debt load, then you stand to save much more money from the use of PSLF. You’re also likely to save more money if you’re able to use Pay as You Earn or the new 10% IBR plan. It’s important to crunch the numbers yourself before committing to a plan.

How do I sign up?

Making use of PSLF is a little strange in that there is no up-front application to be considered for it. You must apply after making the 120 qualifying payments, not before. However, there are methods you can take to organize and verify your qualifying payments while working towards PSLF. The Federal Student Aid Office has recently published an Employment Certification form, which you can fill out and send in, in order to confirm that your employment makes you eligible for PSLF. The form also allows you to officially log the qualifying payments you’ve made thus far. For more details about how you can make use of this form, see The Federal Student Aid Office’s letter for borrowers considering PSLF.

Once you have made all 120 qualifying payments, you’ll need to submit the official PSLF application to have your loan balance immediately forgiven. This application actually does not exist yet. Because the PSLF program was created in 2007 and it takes a minimum of 10 years to complete, the first round of PSLF forgiveness will occur in 2017. The official PSLF application is currently under development, and the Federal Student Loan Office plans to make it available by 2017.

How do I know the program will still exist in ten years?

Unfortunately, there is no guarantee that PSLF will still be around by the time your minimum ten years of payments are completed. The Federal Student Loan Office had this to say on the subject: “The U. S. Department of Education (ED) cannot make any guarantees regarding the future availability of PSLF. The PSLF Program was created by Congress, and, while not likely, Congress could change or end the PSLF program.” The life or death of PSLF is dependent on politics, and as such it’s not entirely predictable what will happen to it. Any one looking to make use of PSLF must grapple with this uncertainty. 2017 is the first year that PSLF will begin forgiving applicants’ loan money. That first wave of forgiveness may invite extra scrutiny of PSLF from congress, and it may see some changes. At this point, however, it’s all a matter of speculation.

Further resources for librarians considering PSLF:

- The American Library Association has a page on Federal Student Loan Forgiveness for librarians which sums up both PSLF and Perkins Loan Forgiveness, the latter of which is a potentially attractive option for title 1 school librarians.

- The Federal Student Aid Office maintains some very comprehensive and helpful pages about PSLF: An FAQ and a fact sheet.

- The Federal Student Aid Office also hosts a page on Income-Driven Plans, the payment plans that you can combine with PSLF. This page contains comprehensive information on Income Based Repayment, Pay As You Earn, and Income Contingent Repayment.

- The PSLF Employment Certification Form and the official instructions for completing it. These documents are used to confirm that your current employment works with PSLF, and to officially log your payments while working there.

- FinAid has a helpful FAQ about PSLF and Income Based Repayment as well as a very useful Income Based Repayment Calculator which can factor in PSLF to help you run the numbers to determine whether the programs are right for you.

- For the final word on PSLF, you can refer to the actual text of the law at the Cornell Legal Information Institute’s online database, filed under 20 U.S.C. § 1087e(m). Be warned, it’s written in legalese.

- It’s also a good idea to find out who your student loan servicer is and contact them for advice on what plans to consider. Their website should have a number you can call for help.

Student loan repayment plans are a complicated matter, and it’s essential that you do a good deal of research before you commit to one. It’s best that you do some math to determine for yourself whether a repayment plan makes financial sense for you.

While I’ve taken great care to be accurate in my reporting, if you have found an inaccuracy, or something I’ve left out, then please don’t hesitate to let me know in the blog comments below! Government programs like this one are often changed and updated, and sometimes outdated or ambiguous facts can survive past their expiration date. Do let me know if one of those facts ended up reaching this blog.

(Post by Derek Murphy)