DRAFT in development

Framework for Collaboration by Laura Saunders is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at http://slis.simmons.edu/blogs/lsaunders/draft-framework-for-collaboration/.

This Framework for Collaboration emerged as the outcome of a series of focus groups with librarians and actual and potential community partners.

The researcher conducted five focus groups over the course of three months, with a total of 22 participants. The participants included eleven librarians and eleven allied professionals and community partners, some of whom had previously collaborated with librarians and some of whom had not. The librarians came from both public and academic libraries and worked in various capacities, including four library directors, reference and instruction librarians, and managers of various departments including access and organization services, research and instruction services, and adult services. The allied professionals and community partners included journalists and writers, a journalism faculty member, the director of a media center, an athletics communications director, a career counselor, the director of a center for excellence in teaching, and an associate director for an academic support center.

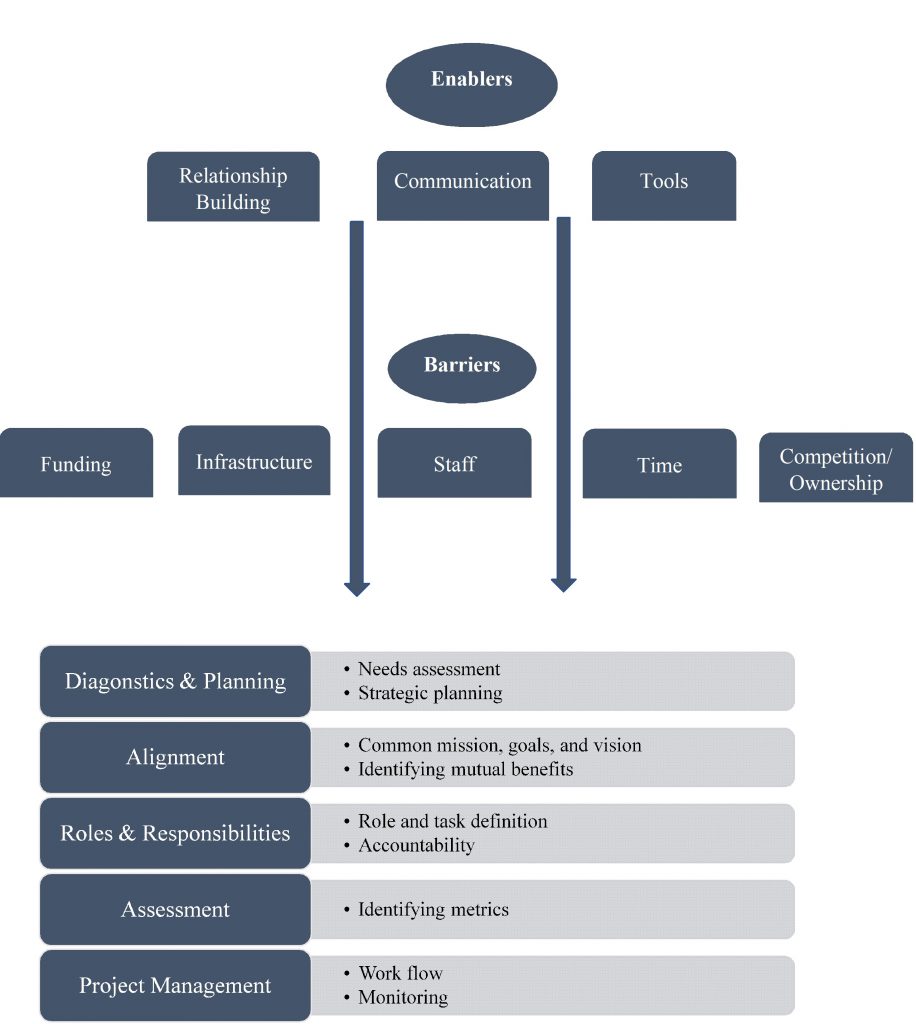

The focus group answers clustered around six themes (Diagnostics & Planning; Alignment; Roles & Responsibilities; Assessment; Project Management; Barriers; and, Enablers), which taken together can form a Framework for Collaboration as depicted in the Figure above.

Each theme is discussed in more detail below:

Diagnostics and Planning

Participants described a range of approaches to collaboration, including “casting a wide net” in order to find potential partners, identifying individuals or organizations with common interests, and having collaborations evolve organically through repeated contact between individuals, departments, or organizations. Participants largely agreed that successful collaboration requires planning, and that planning often begins even before potential collaborators are identified. In some cases, participants indicated that they developed project ideas based on broad interests and trends. For instance, one journalist explained that her organization wanted to build on the Flint water crisis and explore issues of water safety. While it is reasonable to assume that readers would be interested in this topic because of the national attention, the organization did not appear to have formally investigated whether there was an interest among their readership. Likewise, one librarian discussed a personal interest in topics of misinformation and fake news and sought opportunities to collaborate with faculty on his campus around this topic, while a public librarian described tying programming into seasonal or special events like the National Week of Conversation or the anniversary of the Suffrage movement.

In other cases, however, the planning was more strategic, and sometimes involved community needs assessment. For instance, one public library director noted that her library was completing its strategic planning process and that she had identified several key themes that she would like around which she’d like to build programs and services. Part of that strategic planning process involved focus groups that identified community needs and interests, rather than relying solely on the librarians’ perceptions of what would be of interest in their community. Similarly, one woman noted that she had worked in a public library where the director encouraged the librarians to get out of the library and involved in the community, noting “we were very open to sort of meeting community needs.” One academic librarian discussed working with faculty and student support offices to determine student needs.

Another public librarian noted that her library fields many requests from community organizations that are often eager to work with her library and she noted several times that her library is trying to be strategic in selecting potential partners that will work with the mission and goals of the library. As she explained it, “We are always interested in education, arts, and culture, but we’re trying to be actually more strategic in how we describe what a program partnership would be, but more around our mission.” Academic librarians discussed identifying issues and trends on their campuses that could lead to potential opportunities for collaboration. For instance, one librarian noted that her campus was focusing on issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion, and would be requiring faculty and staff to attend a certain number of training sessions on DE&I topics. She worked with human resources and the teaching center to create a guide for faculty to integrate topics of diversity, equity, and inclusion in their classes that would count as a one of the required training.

Part of the planning process involves identifying potential collaborators. This part of the process was more fluid than linear. That is, sometimes participants identified a need or area of interest first and then sought out potential partners with overlapping interests, and other times projects evolved out of contact and communication between potential partners. For example, one public librarian explained that the director of a local media center had come to the library several times to film events and that repeated contact led to the development of joint programming. In other cases, participants sought partners for a particular project. One of the journalists, for instance, discussed targeting certain organizations with whom he wanted to work and pitching ideas to them.

Participants also discussed the need to determine whether to pursue a collaborative project and what level of collaboration was appropriate. While the participants all valued collaboration and the potential benefits of collaborative projects, they also sensed that not every opportunity was equal. For instance, two library directors discussed the issue of being approached by individuals or organizations who wanted to work together and having to decide if collaboration made sense. One of the directors described this as a need to “look underneath the hood” to really understand the idea being proposed, and noted that at times she would have to decide “I’m not willing to invest the time or the energy in this, or the resources. I just don’t think this is going to work, or I think the timing is wrong.”

Similarly, when considering the Tamarack (2017) collaboration continuum, several participants noted that not every project needs to be, nor should be, a deep collaboration. Depending on the project and its goals, sometimes communication or cooperation, as opposed to collaboration, is appropriate. Participants noted that in some cases a relationship with a partner would move up and down the spectrum over time and depending on the needs of a particular project or community. One library director described this movement as being like “an accordion,” where the relationship expands and contracts. As an example, she described being involved currently in an intensive project that she characterized as being high level on the spectrum, in which a variety of partners are sharing expertise and devoting time and resources to develop a major software product. Eventually, when the product is complete, she expects to continue to work with many of the individuals involved, but the relationship at that point will most likely be communication or cooperation rather than collaboration. This participant also stated that it is “really important to be able to recognize when something needs to be moved up or down the continuum.” In other words, there is a diagnostic aspect to understanding when and at what level to collaborate.

Alignment

Once both parties have agreed to pursue a collaborative relationship, participants described the importance of alignment and relationship building to project success. Alignment emerged as one of the most important factors of collaboration, with 104 instances in the transcripts falling into this category. Essentially, alignment has to do with ensuring that the goals, mission, and values of the partner organizations are compatible, that the partners agree on the outcomes of the project, and that the project outcomes align with the goals, mission, and/or strategic plan of any parent organization involved. Throughout all five focus groups participants from all fields stressed the importance of alignment to success, with one participant note “Some of the things that I see when I’m thinking about the successful projects, one is that if the shared goal is a high priority for the people involved.” Throughout the groups, participants discussed alignment using phrases such as “finding of common ground, a mutually beneficial outcome,” “a shared idea or shared mission,” “quid pro quo,” “a common purpose,” and an “overlapping sense of mission and community.”

Roles and Responsibilities

As relationships are built and projects initiated, participants noted the importance of role and task definition. It seemed that in more successful collaborations, the parties involved spent time identifying the roles and responsibilities of each contributor, acknowledging the different expertise and resources that each brought to the project. For instance, one participant described a collaboration between his office and an academic department, noting that as part of the planning they developed a work sheet outlining the various tasks and responsibilities. Another participant described understanding each person’s role and how they fit together to achieve the goals of the project as a sort of puzzle. One participant noted “recognition of what am I supposed to be doing or contributing to this project is particularly important to successful outcomes,” while another asserted that “a lot of successful collaborations really recognize that it’s an ecosystem of work and that everybody has to understand what their role and their contribution is to the overall.”

Related role definition and trust, participants discussed the need for the various partners and contributors to be accountable to one another. While collaboration can lead to many benefits, and usually will be more efficient and cost-effective than solo projects, it does require a commitment of resources including time, staff, space, and/or money from those involved. Those entering into a collaborative project want to know that they will not be wasting their resources and that they will be appropriately supported by their partners. One media coordinator noted that her organization had been “kind of taken advantage of multiple times,” and explained “knowing that it’s not going to be one-sided I think is really important.” Role and task definition is one way of ensuring accountability, as each party recognizes their responsibilities. One participant suggested that developing a Memo of Understanding (MOU) can be “really, really helpful,” because they provide “clear expectations of what we committed to on this day, and you sign on it.” MOUs provide documentation of what the parties agreed to, so if issues come up the parties can return to the MOU to see “what did we agree on?” As one participant noted, it is important to keep track “of who needs to be informed, who’s accountable, who’s just, you know, what are their roles and the weight of their involvement.” Participants noted the importance of trusting each other, but role definition and tools like MOUs seemed to lend a certain accountability that helped enable that trust.

Assessment

Several participants emphasized the role of assessment to the overall success of a collaboration. In particular, these participants noted the importance of identifying metrics for measuring success. Some of the participants spoke about metrics specific to particular projects. For example, one library director talked about partnering with schools in order to provide students with better access to information that would lead to better research on their assignments as well as greater return on investment for library databases. Others talked about some of the general benefits of collaboration, such as increased visibility, good public relations, and reaching new audiences. One participant stressed the importance of being realistic about the scope and scalability of projects and the potential impact they will have. One participant said that motivation for collaborating would be “knowing that you’re gonna both benefit more than if you just went at it alone.” Other participants stressed the importance of defining “what are the deliverables,” or the “key points of delivery and known measures of success.” However they described assessment, these participants seemed to be making the point that collaboration is not an end in itself. In other words, they did not necessarily see value in pursuing a partnership simply for the sake of collaborating, but they wanted to define the mutual value and benefits in a measurable way so that they could determine in the end if the “whole is more than the sum of its parts.”

Project Management

Not surprisingly, throughout the focus groups, participants pointed to the role of project management for successful collaboration. As described above, these participants recognized that collaborations are often complex, involve multiple parties with different roles and responsibilities, and require a level of trust and accountability. As such, they emphasized the need to implement various project management techniques to ensure that work is being tracked and everyone is held accountable. One participant asserted the importance of “setting up a structure where people can get from one step to the next step to the step and not necessarily have to do a lot to follow that path, which obviously requires a lot of front end infrastructure.” Specifically, participants mentioned the need to document meetings so there is a record of discussions and decisions. As one participant explained, “You need to be able to keep track of everything, especially on something that’s multiple stakeholders, multiple timing. You don’t want to keep going back and having the same meeting over again.” Participants also discussed the need to develop budgets and timetables or schedules. For example, as noted above, one participant described developing a task sheet that laid out the roles and responsibilities for all parties involved in a career fair. The project management aspects of collaboration seem to overlap with defining roles and responsibilities and assessment, and contribute to the sense of accountability and trust among partners.

Barriers

One of the main barriers to collaboration identified by focus group participants was infrastructure, which included resources of time, money, and staff. Budget was of particular concern. Across the board, participants pointed to lack of funding as a barrier to collaboration. As one participant noted, “there’s no shortage of ideas… but who’s gonna pay for them?” This participant also discussed the amount of time he spent in search of funding, including writing grant proposals. At the same time, however, some participants viewed collaboration as a way to alleviate budget pressure, if projects involved cost-sharing. Many participants also noted that staffing shortages made it difficult to devote time to developing relationships and carrying out the tasks of a collaborative project.

Competition or ownership also emerged as a potential barrier for some projects. Several participants noted that in some cases people or organizations seemed unwilling to share information and ideas, perhaps because they wanted to keep ownership of them. These participants said that issues of ownership and competition were not prevalent in the higher education and non-profit worlds in which most of them worked, but some of them recalled such issues from previous experience in the corporate world. With that said, a couple of the participants from higher education indicated that they had experienced some issues of ownership within academia. Some of these participants suggested that faculty might be hesitant to collaborate in the classroom because of limitations on their time and because of the amount of material they have to cover, while others thought that faculty involved in research might not want to share ideas for fear of “being scooped.” Whatever the reason behind it, ownership was seen as a barrier since it deterred people from engaging in the information sharing and relationship-building necessary for collaboration, and suggested a lack of trust.

Enablers

While participants were clearly aware of the barriers to collaboration, certain enablers also emerged from their discussions, including communication, relationship-building, and tools. By definition, a collaboration involves more than one party, which means that individuals or organizations interested in collaborating need to identify and build relationships with potential partners. Part of the process of relationship-building includes developing an understanding of and sensitivity to the cultural differences across the organizations with whom the participants find themselves collaborating. In terms of cultural sensitivity, participants discussed the importance of understanding each other’s work practices, priorities, and language. As one library director summed it up “I do think that some partnerships—and it depends on the nature of the partnership—culture needs to be addressed.” She noted, for instance, that when her public library collaborated with a community organization that charges for services the two organizations needed to figure out how to respect each other’s funding priorities. Some participants noted that potential collaborators do not always have a good sense of the mission or roles of different organizations or even different departments in the same organization. One participant noted “if we understood better what the other folks were doing it would be easier to collaborate.” Another stressed the need to “understand everyone’s domain expertise” and to “parlay what you’re doing into their world and vice versa,” ultimately explaining that “a lot of it is a translation exercise of one platform to another.” One academic librarian framed the issue as one of communication and the need to develop a shared vocabulary, contending “it’s partly it’s just discovering the language that’s gonna actually hook somebody.”

Learning each other’s culture is only a first step, however, toward building relationships. Several participants stressed the importance of cultivating relationships both in order to begin a collaboration and to sustain one over time. They maintained that people needed to respect each other, trust each other, and feel valued, in order to be able to work together effectively. One participant described it as viewing collaborators as part of a team, even if there is a differing power dynamic. For example, she said she never describes people as working for her, but says that they work together. Along the same lines, another participant noted the importance of feeling appreciated by her team and of expressing appreciation for the work others do. One public library director summed it up this way: “I do think it’s like having—a really good partnership is like—a baby in a way, because you have to really feed not only the work we’re doing but also the relationship in a partnership, especially if it’s a long-standing, like you’re gonna go back and back time and time again.” Developing trust across organizations was identified as an important part of relationship-building.

Communication is important throughout the collaboration process, from reaching out to potential partners through the final assessment of the project. Participants noted the importance of just initiating conversations as a way to reach out to and get to know potential partners. They discussed the role that brainstorming can play in idea generation, as people “add their two cents” or “feed off of each other or collaborate together for ideas.” They also recognized the importance of active listening, “really hearing what other people say,” as a part of communication. They also emphasized the need for both support and appreciation of contributions and honest feedback. On the one hand, acknowledging each other’s expertise and hard work is important to sustaining morale and contributing to building trust and relationships. At the same time, however, participants recognized that projects were less likely to succeed if partners were unwilling to provide or accept constructive feedback. For instance, one participant described having “post-mortems,” in which participants discussed their experiences of the project. He noted that it was important to manage these discussions so they were constructive and did not turn into a “gripe-fest.” Likewise, another mentioned the importance of sharing experiences and “having that hard conversation.” One participant described a failed collaboration as resulting at least in part from the fact that the people involved had not been willing to offer each other constructive critiques. These participants seemed to view honest feedback as part of assessment and as a way to improve the project and the relationships.

Finally, participants talked about tools, both publicly available and home-grown, that enabled or facilitated collaboration. For instance, a number of participants discussed the role social media can play in collaboration. One participant described using social media to pitch ideas and seek potential collaborators. Another relied on a closed Facebook group to share ideas, get answers to questions, and find support from colleagues. Some participants also found productivity tools such as Google Drive helpful in organizing and sharing documents with partners. Other participants had developed tools in-house. For instance, one public library had developed a proposal form for potential partners to pitch ideas. Another participant talked about creating templates for documents such as MOUs to make them easier to implement. The particular tools varied depending on the project and the task, but what was consistent was the importance of these tools in facilitating communication and streamlining processes.