So far, Unbound’s InfoFuture-inspired series on library-based artist residency programs has looked at academic libraries and public libraries. Today, we’ll be considering a less common venue for such programs, the archives. When a public archives in Portland, Oregon brought artists in to interact with their collections, they discovered just how effective an artist-archives partnership can be.

The city of Portland’s main budgetary allowance for public art comes from their Percent for Art program, which dictates that 2% of most publicly funded construction projects must be spent on public art. When the City of Portland Archives & Record Center (PARC) moved to a new location on the Portland State University campus in 2010,they collaborated with Portland’s Regional Arts & Culture Council (RACC) to dedicate a part of their Percent for Art allowance to the creation of an artist in residence program.

In 2013, PARC began their first artist residency, welcoming visual artist Garrick Imatani and poet Kaia Sand. “Imatani and Sand, who share a connection in their approaches to documentary research–based work, their interest in politics and history, and their long histories of working in archives as part of their creative processes, applied for the residency as collaborators.” (Carbone, 2015, p. 30)

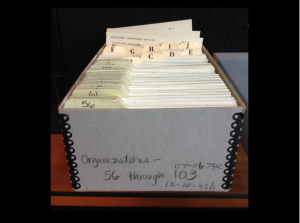

The pair were fascinated by one of PARC’s most unusual collections: The Watcher Files. From the 1960’s through the 1980’s the Portland Police Bureau conducted extensive surveillance on non-criminal civic and activist groups. Once a 1981 law made such practices illegal, the police’s records of it were ordered to be liquidated. One of the detectives involved in conducting the surveillance stole 36 boxes of the records and hid them away before they could be destroyed. Decades later, an anonymous source donated them to the archives, where they were accessioned.

The Watcher Files include surveillance of 576 organizations, including anti-nuclear activists, feminist groups, a voter registration project, and even a bicycle repair collective. These documents are immensely relevant to today’s concerns about privacy, unchecked surveillance, and police militarization. Inspired, the artists set to work translating the aesthetics and ethical implications of the records into art. The art they produced lent the records an immediacy and emotional resonance that the public does not often see in a civic archive’s collections.

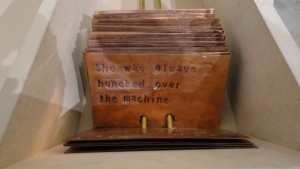

Sand’s poem She had her own reason for participating was a reaction to the disturbing number of surveillance documents on feminist activists she found in the collection. The poem took the form of a card catalogue drawer, with each line imprinted onto a copper card. The drawer was built into a gallery plinth fashioned by Imatani to resemble a cardboard archival storage box, geometrically warped. Every line of the poem is a statement quoted from the records beginning with the word “She”. In the poet’s words, “This poem forms a small populace of women—women who organized dissent; women who labored; women who suffered violence and imprisonment; women engaged in struggles during my girlhood years when I learned to be proud of a legacy of feminism, unaware of just how threatening those with power found feminism.”

She had her own reason for participating was not the residency’s only piece to use archival aesthetics in its presentation. At their gallery showings, the artists employed archival materials to present their art. Imatani constructed several pieces of furniture modeled after what they’d seen at PARC, including desks etched with Sand’s poetry, housing drawers containing framed works. Another of Sand’s poems incorporated redacted lines, to recall the redacted sections of the surveillance files. By fashioning their art after the aesthetics of the archives, the artists invited gallery visitors to “experience and interact with the archive, public art, and Portland history” (Carbone, 2015, p. 45). In this way, the shows familiarized gallery visitors with the archives, its holdings, and its methodology.

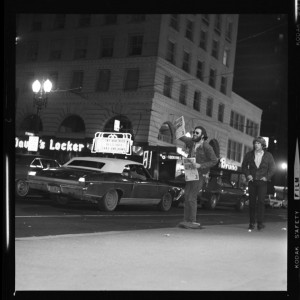

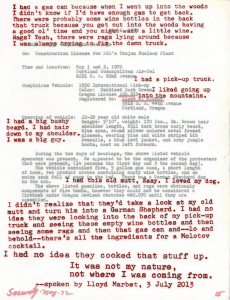

The residency at PARC was also noteworthy for radically dissolving the boundary between an archival record and its subject. As they familiarized themselves with the Watcher Files, Sand and Imatani began reaching out to locals who had appeared in the surveillance records decades ago. They soon initiated a working relationship with a former anti-nuclear power activist named Lloyd Marbet. Even though his methods of protest were legal and non-violent, he appeared several times in the Watcher Files. The artists showed Marbet the surveillance records about him, and allowed him the chance to respond, over forty years later. His remarks on the documents were screenprinted onto sheer paper, and placed over the originals, marking them up with his annotations.

In one 1972 document, the police listed the contents of Marbet’s truck, and noted that it contained empty wine bottles, gas cans, and rags, “obviously components of fire bombs.” In his response, pictured below, he explained that the gas was extra fuel for long trips into the woods, the wine bottles were left over from those trips, and the rags were there to help him fix the truck when it broke down. “I had no idea they cooked that stuff up,” he said, “It was not my nature, not where I was coming from”

It is vanishingly rare that an archival document’s subject has a chance to respond to it so directly. Marbet’s mark-ups overcame an extreme power imbalance. He was watched against his will by one state institution (the police), and their unchecked, unflattering observations were then placed into another state institution (the archives) to persist as historical record. Marbet had no input into this process, and for much of the time was purposefully kept unaware of it. By allowing him the chance to respond, PARC and its resident artists shifted this power dynamic in a more fair direction. The marked-up document is not just good art, it’s also a strong meditation on archival ethics, and an example of a potential solution to an ethically dubious situation.

Sand and Imatani created several other excellent works during their PARC residency, including some fascinating poetry performances, a beautiful letterpress printed book, and a handmade bookshelf containing book recommendations by local activists. Their residency ended in February of 2015. I reached out to Diana Banning, Portland’s City Archivist, and she was very positive about the experience: “The first residency with Sand and Imatani was wildly successful, and not just because of the fabulous art and poetry created. They served as excellent ambassadors for our archives, and were able to generate interest and energy within the artist, activist, and archival community.”

PARC has plans to bring in a second artist residency. They currently expect it to begin in January 2016 and run for twelve months. Depending on future funding, they expect to host at least two and potentially up to four more residencies in the future. It will be exciting to see where they take this innovative program!

——–

- The Watcher Files Project has its own website where you can find out more about Sand and Imatani’s work from their residency.

- For more information about PARC and their upcoming events and programming, check out their website.

- This article was inspired by and informed by Kathy Carbone’s excellent article about the residency:

Carbone, K. (2015). Artists in the Archive: An exploratory Study of the Artist-in-Residence Program at the City of Portland Archives & Records Center. Archivaria, 79, 27-52. - RACC has just posted the RFQ for the second artist-in-residence program at PARC! The deadline for an artist to apply is 9/28.

——–

(Post by Derek Murphy)